For this month, we’re excited to announce our March pick is Lebanese writer Elias Khoury’s celebrated 2018 novel, “Children of the Ghetto: My Name is Adam.” The book is an epic novel that follows Palestinian ex-pat Adam Dannoun and his brush with Blind Mahmoud that spurs an exploration of the past, and what happened to his hometown, the “ghetto” of Lydda in 1948. The story is told through the device of Adam’s found notebooks, that are rich in references to Israeli and Palestinian literary giants. For Khoury who was born in 1948 in Beirut, the novel marks as a dive into the events that surrounded his upbringing in Lebanon, and later move to Jordan during the late 1960s that abruptly ended after Black September.

When purchasing your copy of “Children of the Ghetto” use the promo code MONDOWEISS at checkout for a 30% discount.

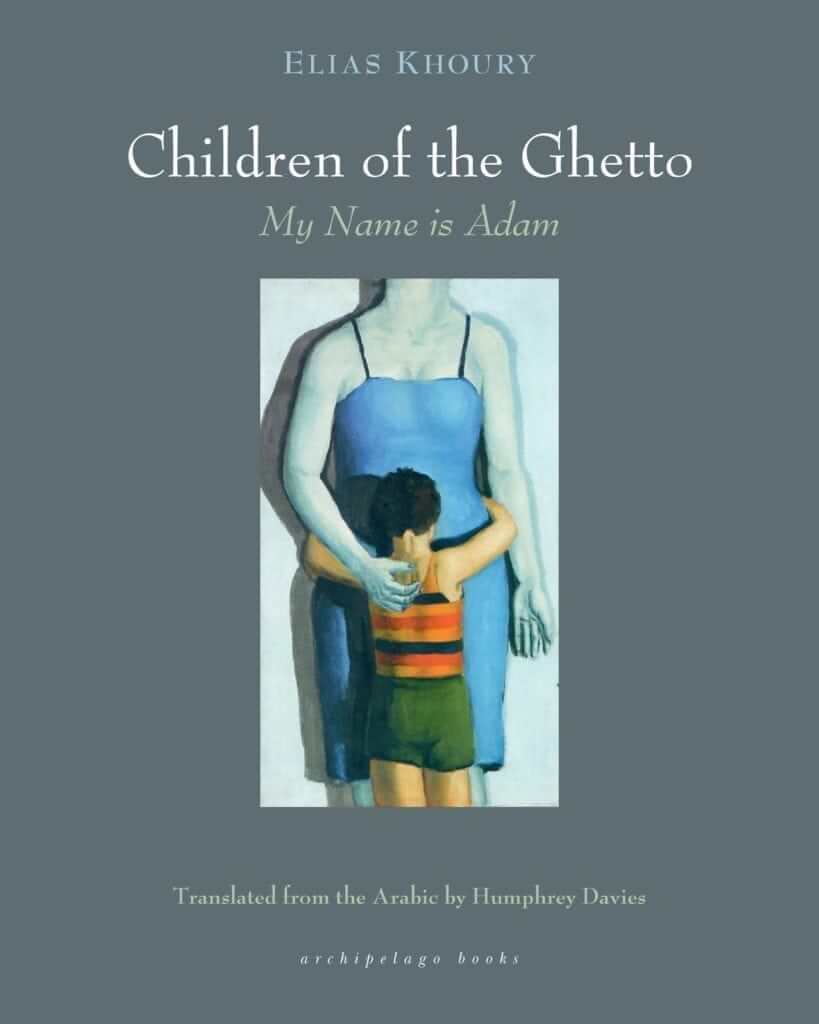

CHILDREN OF THE GHETTO

My Name is Adam

by Elias Khoury and translated from Arabic by Humphrey Davies

400 pp. Archipelago Books. $20

Copyright © 2020 by Elias Khoury, translated by Humphrey Davies, from Children of the Ghetto: My Name is Adam. Reprinted by permission of Archipelago Books.

Waddah al-Yaman

(POINT OF ENTRY 1)

HE WAS A poet, a lover, and a martyr to love.

This is how I see Waddah al-Yaman, a poet over whose lineage, and very existence, the critics and the chroniclers of his verses differ. To me, though, he represents the most extreme sacrifice of which love is capable – a silent death. The poet kept silent because he was trying to protect his beloved, and the coffer of his death, in which the caliph al-Walid ibn Abd al-Malik interred him, was the coffer of his love.

The title of the novel will be The Coffer of Love, and I’m not going to play the allegory game with it. Love is the most sublime of all the emotions – their lord and master, indeed – and is what gives things meaning. Only love and words give meaning to life, which has none.

No, I refuse to write an allegory, and the reader who searches for the Palestinian symbol in Waddah’s history will find instead a human parable relating to Palestinians, Jews, and all men that have been per secuted on earth.

I don’t want to go on about semantics – I’m not confident of my ability to write anything on the topic – but whenever I read contempt or criticism in the faces of my Israeli friends, or in Israeli texts, for the Jews of Europe that were driven to the slaughter like sheep, I almost choke. I think the image transforms them into heroes and the hollow criticism directed at them only points to the folly of those who think that the power they possess today will last forever; indeed, that contempt may have been the first sign of the racism that would later spread like an epidemic through Israeli political society.

That discussion is of no interest to me. I love the image of the slaughtered sheep – an emotion I may have acquired from my Christian mother who, whenever she looked at the picture of her brother Daoud, who’d been lost to exile, would say he looked like a sheep because there was something about his features of the Lord Jesus. The idea for the story had nothing to do, however, with the “sheep that is driven to the slaughter and never opens its mouth,” as per the prophet Isaiah; rather, it was conceived when I saw Tawfiq Saleh’s movie The Dupes, a Syrian production directed by an Egyptian and based on the novel Men in the Sun by Ghassan Kanafani, a Palestinian. The movie shook me to the core; it made me reread the book and decide to write this story.

I didn’t like the cry of protest at the end of the novel. The three Palestinians who got into a water tanker, driven by a man whose name and appearance are shrouded in mystery, died of suffocation in the tank, in which they were supposed to be smuggled from Basra in Iraq to the “paradise” of Kuwait. They died in the furnace of the cistern before crossing the Iraq–Kuwait border and they didn’t make a sound, causing the author to scream into the driver’s ears a near stifled “Why?” The Egyptian director, Tawfiq Saleh, changed the ending though, so that instead of us asking the three Palestinians why they hadn’t banged on the sides of the tank, we instead see their hands banging away on the sides of the tank.

The banging, however, is meaningless as it would have been impossible for the Kuwaiti border officials, barricaded inside their offices, their ears deafened by the sound of the air conditioners, to hear any thing, thus making the real question not the silence of the Palestinians but the deafness of the world to their cries.

I’d thought the perspective from which I would write my novel would be different: I wouldn’t devote a single word to Palestine and that would save me from the slippery slope that turned Kanafani’s novel into an allegory whose elements you have to deconstruct to get to what the author wanted to say.

I don’t feel comfortable with messages in literature. Literature is like love: it loses its meaning when turned into a medium for some thing else that goes beyond it, because nothing goes beyond love, and nothing has more meaning than the stirrings of the human soul whose pulse is to be felt in literature.

I repeat: literature exists without reference to any meaning located outside it, and I want Palestine to become a text that transcends its current historical condition, because, based on my long experience of that country, I’ve come to believe that nothing lasts but the relation ship to the adim – the skin – of the land, from which derives the name of Adam, peace be upon him, that they gave me when I was born. My name goes back to the father of mankind, the first signifier that binds man to his death.

Waddah al-Yaman fashioned an astonishing love story, one unsure passed before or since. He was unique among his kind – a poet who played with words, rested on rhymes, rode rhythm. In the end, he decided to keep silent to save his beloved and died as the heroes of unwritten stories die. It never occurred to him to bang on the sides of the coffer, and I, unlike Kanafani, will never ask him that wretched “Why?”

I shall let him die and shall live his last moments in the coffer with him, and I shall give his mistress – for whom Arabic literature provides no name other than the conventional Umm al-Banin, or “Mother of the Sons” – a name, and so make of her death a final cry of love that will ensure the story a place in the ranks of those of “the lover’s demise.” This mistress – the caliph’s wife – was, I hereby declare, called Rawd, meaning “meadow.” I give her that name because the poet’s love for her began with a confusion over names, in that, following the death of his first beloved, Rawda, he found in Umm al-Banin both his meadow and his grave, and the two beloveds, both killed and both killers, became confused in his mind, and he himself, through the silence that he chose as the correlate of his verse, became the victim, for the only correlate of poetry are the interstices of silence, whose rhythms are matched precisely to those of the soul.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

March 9th, 2021

March 9th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: