Eighty years ago, the Netherlands became the first and only Nazi-occupied country to organize a nation-wide strike to protest the persecution of its Jewish citizens.

The so-called “February Strike” was the first large-scale public protest against Germany’s assault on Europe. Remembrance of the event has evolved over the decades from a narrative of Dutch resistance to the more complicated narrative of the Holocaust, in which 100,000 Dutch Jews were deported and murdered.

At the time of the strike, the Netherlands had been occupied by Germany for nine months. The immediate catalyst was the Germans’ pogrom on Amsterdam’s Jodenbuurt neighborhood, in which 425 Jewish men were arrested and deported.

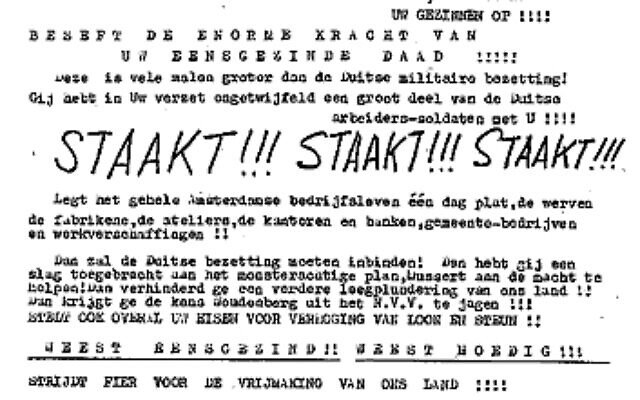

After a nighttime planning meeting, strike organizers delivered flyers to factories urging workers “to show solidarity with the Jewish part of our society that has been hit so hard.” With a rallying cry of “Shut down Amsterdam for a day,” the movement spread to several Dutch cities and paralyzed the country.

Although the February Strike did not make Germany alter its plans regarding the Jews, the nascent Dutch resistance movement gained traction and inspiration from the solidarity shown during three days of protest.

As Dutch historian Bas Kortholt told The Times of Israel, recent events in the United States have some similarities to the strike movement 80 years ago.

“It is always difficult to compare historical events,” said Kortholt, a long-time researcher at the former transit camp Westerbork’s museum.

“But if you compare the strike and for example, the Black Lives Matter protests in the summer, you see that both have had a strong symbolic function,” said Kortholt, a member of the Netherlands’ delegation to the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance.

“Both events inspired people on a large scale to speak up and state their opinions in different ways,” said Kortholt.

‘Shut down all of Amsterdam’

The first Dutch protests against the Nazis’ persecution of Jews came at the end of 1940, when students in Leiden and other cities decried the removal of Jews from public positions, including universities.

German pogrom on Amsterdam’s Jewish Quarter in February 1941 (public domain)

By early 1941, the Dutch pro-Nazi organization — called “NSB” — was sending “defense division” gangs into Jewish neighborhoods to terrorize the population. In response, the Jewish community organized gangs of its own for protection against the Dutch version of Germany’s “Brown Shirts.”

In early February, fighters from Jewish and NBS groups held a “pitched battle” in which an NSB member — Hendrik Koot – was mortally wounded. The altercation, along with several others, led the Germans to cordon off the Jewish quarter with barbed wire. The canal bridges were pulled up and checkpoints installed to prevent the entry of non-Jews.

On February 23, the city’s Nazi occupiers conducted their first pogrom. During two days of violence, 425 Jewish men — all of them aged 20-35 — were arrested and deported. All except two of them perished at Mauthausen or Buchenwald.

Nazi parade in Amsterdam, early in Germany’s occupation of the Netherlands. ‘The Beehive’ department store, Jewish-owned before the occupation, is seen in the background. (public domain)

With the Germans’ intentions toward the Jews clarified, the outlawed Dutch Communist Party decided to organize a strike. On the evening of February 24, a meeting was held in the Jordaan neighborhood with Communists and union representatives. It was decided the next day’s strike would “shut down all of Amsterdam for a day.”

First to strike the next morning were tram workers, in order to paralyze transportation. Sanitation crews and dockworkers followed. Later in the morning, factories and stores closed.

The Germans were caught off-guard by the strike as it spread beyond Amsterdam to other Dutch cities. The Nazi-appointed Jewish Council, based in Amsterdam, pleaded with the Communists to end the strike, fearing additional deportations.

Organizing the ‘February Strike’ in Nazi-occupied Amsterdam, Netherlands, 1941 (public domain)

By the second day of protest, the Germans were retaliating with rifles and hand grenades. Nine strikers were killed and hundreds wounded by the third day when the movement was snuffed out.

‘A task with hardships laden’

A few weeks later, the Nazis executed 18 Dutch resisters — including three of the strike leaders — on the sand dunes. Dismissed from their positions were Amsterdam’s mayor, the city council, and municipal workers seen as disloyal.

The executions significantly affected the public’s mood. For example, a memorial “poetry card” called “The Song of the Eighteen Dead” was published and sold to raise funds for Jewish children in hiding. The song was written by Jan Campert, who died at Neuengamme for the crime of aiding Jews.

Jan Campert (public domain)

“I knew the task that I began, a task with hardships laden, the heart that couldn’t let it be but shied not away from danger,” wrote Campert. “It knows how once in this land freedom was everywhere cherished before the cursed transgressor’s hand had willed it otherwise.”

From “poetry cards” to later examples of armed resistance, the February Strike remained a powerful symbol throughout the war, including during the “Hunger Winter” famine when Germany starved out portions of the Netherlands.

“In this sense too, the strike is important,” said Kortholt. “The effects of the strike were long felt, not only in 1941, and became a symbol for former resistance fighters during and after the war.”

In 1952, “The Dockworker” statue was unveiled to commemorate the strike. The figure of a portly, middle-aged worker was intended by sculptor Mari Andriessen — a former resistance activist — to represent the “everyday” strikers of 1941.

‘Dockworker’ statue and Portuguese Synagogue in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, January 2018 (Elan Kawesch/The Times of Israel)

Located in front of the Portuguese Synagogue where the Jodenbuurt raids took place, “The Dockworker” plays a similar function to The Anne Frank House across town. At both sites, the virtues of wartime resistance are elevated.

“During the 1950s and ’60s, the narrative was predominantly about the resistance and the strike was one of the most well-known and most used symbols in remembering the war,” said Kortholt.

‘Anne Frank and Auschwitz’

Beginning in the 1970s, Dutch memory of the war made more space for the Holocaust. In addition to resistance, people started to discuss the role of collaborators and how the country’s bureaucracy enabled Germany to murder five out of seven Dutch Jews.

“Beginning in the 1970s, the perspective of the memory of the war shifted to the Holocaust,” said Kortholt. “Today most of the general public know about Anne Frank and Auschwitz, while especially amongst young people knowledge about the strike — and other resistance events — is fading.”

The Dutch Auschwitz Memorial in Wertheim Park in Amsterdam, November 2015 (Matt Lebovic/The Times of Israel)

Throughout World War II, Dutch support for the Nazis ran high, with the pro-Nazi NSB organization boasting 101,000 members at its peak in 1944. Some of those members helped “round-up” Jews in hiding — including as “bounty hunters” paid by the Germans.

In recent years, many anti-racism and anti-bigotry protests have been held at “The Dockworker,” expanding the statue’s “universal” meaning. In Kortholt’s assessment, recent events in the US could also serve a symbolic function to inspire future action.

“It will be interesting to see if the memory of the Black Lives Matter protests or the events in Washington this month will take a likewise ‘path’ as the memory of the strike has taken,” said Kortholt.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

February 20th, 2021

February 20th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: