As the Claims Conference for Materials Claims Against Germany released disturbing new research about the state of Holocaust memory this week, the New York-based Olga Lengyel Institute (TOLI) deployed the artwork of teenagers to preserve Holocaust memory.

The U.S. Millennial Holocaust Knowledge and Awareness Survey demonstrated the spread of lies and distortions related to the genocide across America, including that Jews were the Holocaust’s perpetrators. For TOLI board member Harry D. Wall, the findings were a jarring call to action.

“It’s a wake-up call for redoubling our efforts for Holocaust education, and also how we engage students and teachers,” said Wall. “[The poll was] deeply troubling, revealing not only lack of knowledge, but also susceptibility to distortions about the Holocaust, much of it on social media,” said Wall.

Called “How High School Students See the Holocaust,” TOLI’s new online exhibit received 140 submissions from around the world, said Wall. According to the institute’s Marni Fritz, who coordinated the project, art can help students navigate the unspeakable aspects of the Holocaust.

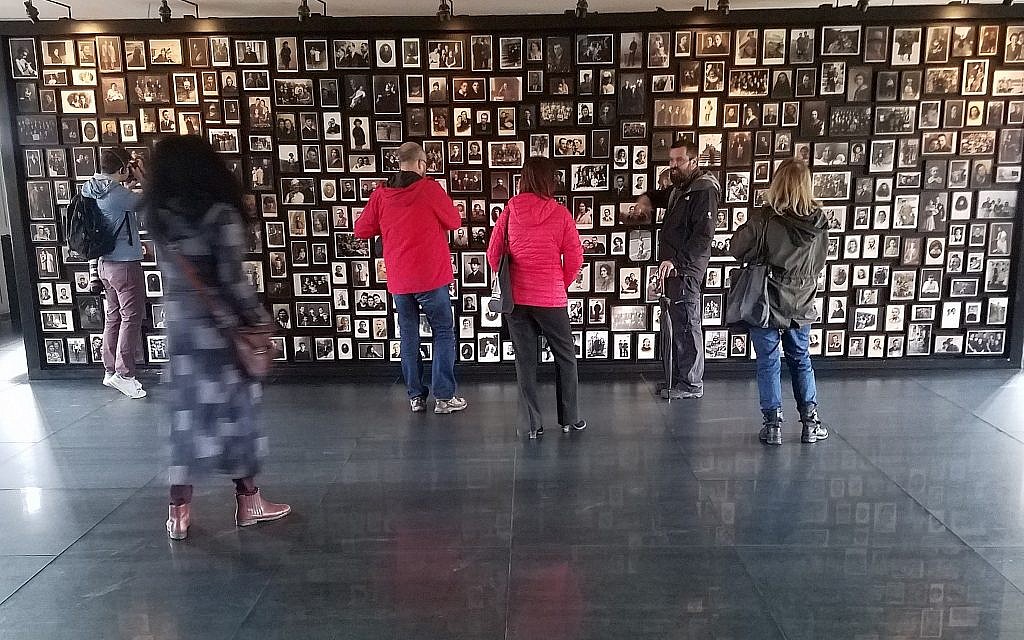

Illustrative: A Holocaust memorial created in the ‘sauna’ facility of the former Nazi death camp Auschwitz-Birkenau, in Poland, with photographs of people deported there, October 2017 (Matt Lebovic/The Times of Israel)

“Using art to teach about the Holocaust challenges us to confront the emotional impact these lessons have on us as individuals and our history,” said Fritz, who manages social media and fundraising for the institute.

This was the first year the institute organized an art exhibit, said Fritz, and teachers are being encouraged to use the art in “virtual” classrooms.

Among the submissions to the exhibit, one that stood out to Fritz was “Genocide,” by Madeline Dittman. A student in Parkland, Florida, Dittman “was inspired by eyewitness testimony and she produced a haunting portrait of various hands and feet entwined, contextually separated from the rest of their bodies,” said Fritz.

‘Genocide’ by Madeline Dittman, a submission to TOLI’s online art exhibit (courtesy)

“On these hands and feet we see pain, evidence of hard labor, and fading life,” said Fritz the image. “This is such a raw representation of human suffering and adds an incredible nuance to the emotional aspect of survivor’s experiences.”

Some of the submissions include background writings from the artist, allowing students to explain symbolism, emotions, and context. Many entries featured yellow Stars of David, barbed wire, and boxcars, evoking the genocide’s brutal materiality.

TOLI was named for Olga Lengyel, an Auschwitz survivor who wrote “Five Chimneys,” one of the first post-war accounts of the German Nazi death camp where one million Jews were gassed. Years later, Lengyel’s testimony helped inspire the novel, “Sophie’s Choice.”

Moving to New York after the war, Lengyel believed “education was crucial to understanding the Holocaust and preventing such atrocities from happening again,” said Wall.

‘Where are the Jews?’ is a submission to TOLI’s art exhibit from Bulgaria (courtesy)

After Lengyel’s passing in 2001, the teacher training program was founded and later named after her. Starting in New York, the seminars expanded around the US and then to Europe, with 2,800 teachers having completed one.

“We want to provide teachers, in rural as well as urban areas, with the possibility of Holocaust education,” said Wall. Seminars have taken place in Jackson, Mississippi and Billings, Montana, as well as Ferrara, Italy and Vilnius, Lithuania.

“In Europe,” said Wall, “where the Holocaust took place, about one-third of respondents in a survey said they know ‘little or nothing about the Holocaust.’ And this ignorance is accompanied by a surge in anti-Semitism.”

‘It’s not just about the Holocaust’

“Art is one of several means to reach students, and to enable children to express themselves,” said Wall. “The Holocaust is a complex issue that is unthinkable and stretches the limits of understanding human nature. The key is to make it less abstract without trivializing it.”

The Holocaust is a complex issue that is unthinkable and stretches the limits of understanding human nature

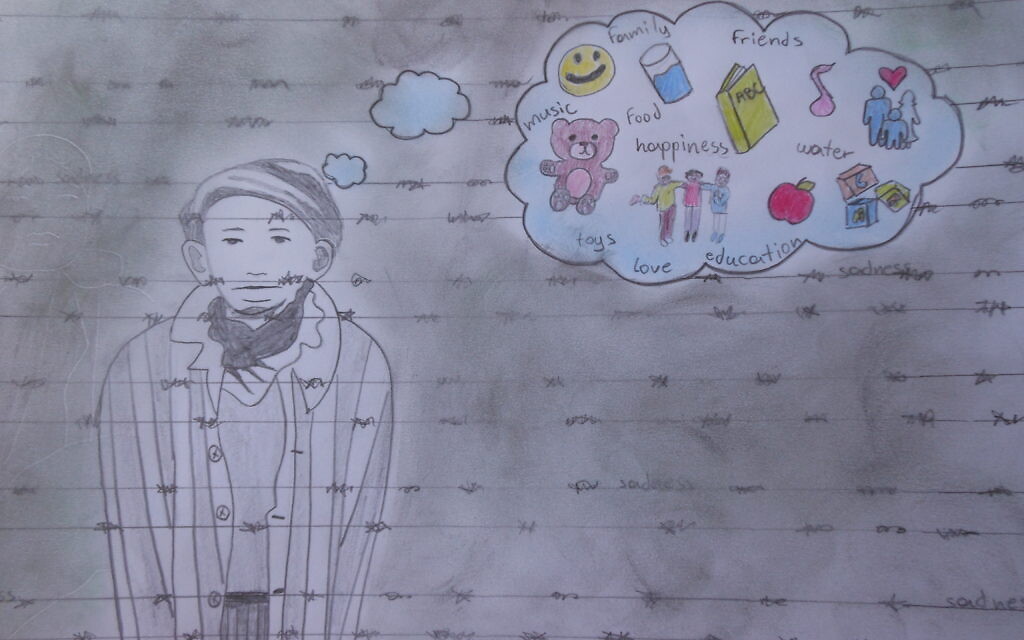

As an example, Wall pointed to a high school student’s drawing called “Jews of Thessonaliki,” depicting the plight of Jewish-Greek children imprisoned by the Nazis.

“This drawing, by a high school student in Kilkis, Greece, is so poignant,” said Wall. “A child prisoner behind barbed wire, dreaming about family, play, food and music captures the tragedy as only another child could do.”

A student in Greece reflected on the Nazi persecution of Jewish children in an entry to TOLI’s 2020 online art exhibit (courtesy)

According to Wall, the institute has organized Holocaust education seminars in 15 cities across the US. With modules for middle school, high school, and college educators, the focus is on preparing teachers.

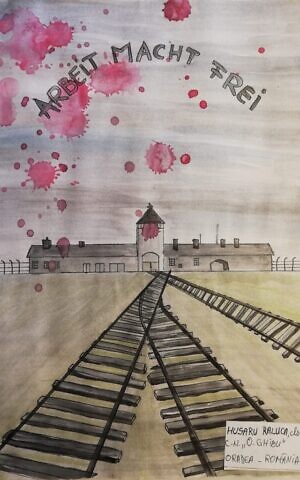

‘The Iron Road of Death,’ a Romanian student’s submission to TOLI’s online art exhibit in 2020 (courtesy)

“What we do is invest in the teachers,” said Wall. “Our national seminar in New York is 12-days of professional development. The satellite seminars, programs from Mississippi to Montana, are a five-day commitment from teachers,” he said.

Working in eastern Europe has given TOLI insight into the challenges of introducing Holocaust memory to places where it was been distorted, said Wall.

“We find there are teachers who come from cities where there was a significant Jewish population, but they know almost nothing about that heritage and the Holocaust,” said Wall.

“And where they did learn about the Holocaust, it was often as a ‘foreign’ atrocity, carried out by Nazis. Nothing about their own population, which collaborated, all too willingly, with the Nazis in the extermination of their Jewish communities,” said Wall, mentioning Romania, Lithuania, Ukraine and Poland as countries where seminars take place and the need is greatest.

From the Nebraska Correctional Center for Women, a graphic representation of the novel ‘Five Chimneys’ by Olga Lengyel

“The more that educators are provided with resources, the more Holocaust instruction, we believe, will be brought into the classroom,” said Wall. “And it’s not just about the Holocaust. It’s also the lessons that apply in today’s world, such as anti-Semitism, racism and other forms of intolerance.”

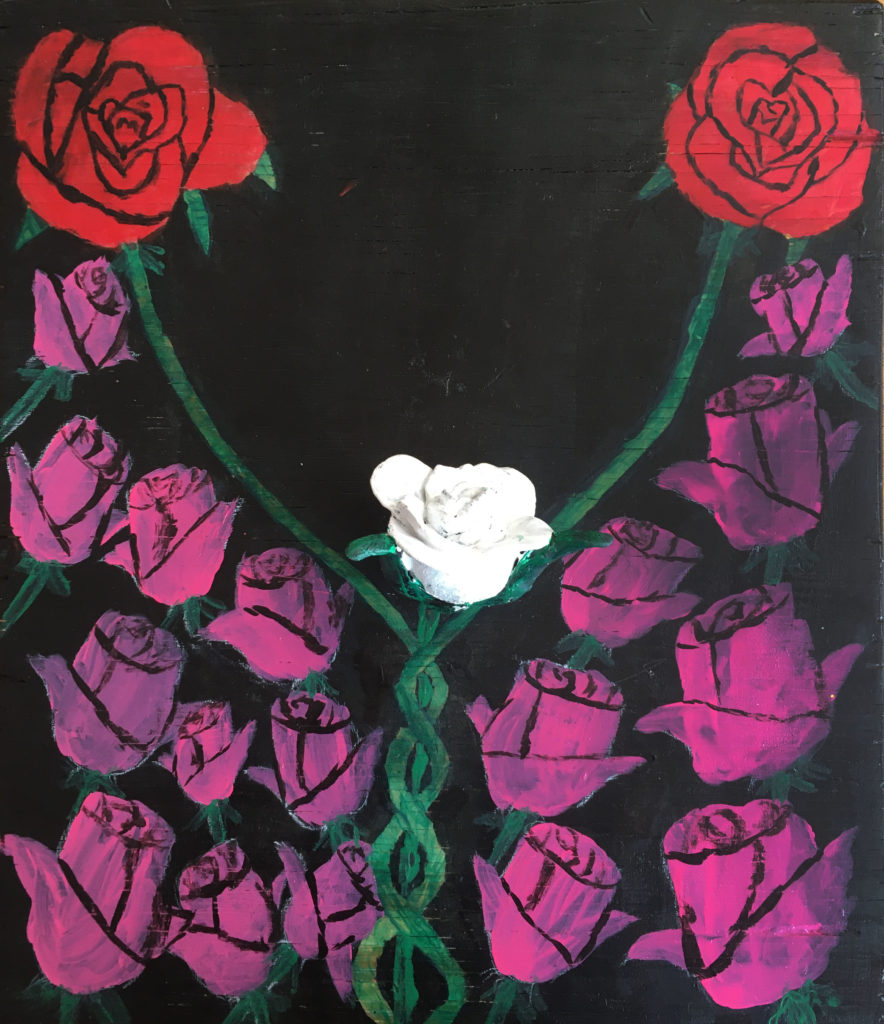

According to Marni Fritz, the exhibit demonstrates the potential for Holocaust education to help students process their own moral choices. In one entry, a student’s collage of roses was symbolic of the number of perpetrators and bystanders during the genocide, as compared to the number of upstanders who helped victims.

“These art pieces act as inspiration for our younger generations confronting hate and bigotry, as well as embracing human rights and social justice in very uncertain times,” said Fritz. “Pieces like this one give us hope.”

An untitled submission to TOLI’s art exhibit from

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

September 22nd, 2020

September 22nd, 2020  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags:

The ashkeNAZI German jews and what they did to the Europeans.