Scientists affiliated with the GLOBE Institute’s GeoGenetics Centre at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark have created an Artificial Intelligence program that is helping them identify ancient mutations in the human genome. As they explain in an article in the online journal eLife, they are using this program to find out more about the genetic materials modern humans inherited from archaic hominin species, particularly noting the DNA inherited from our long-extinct cousins the Neanderthals and the Denisovans.

The scientists use the term “adaptive introgression” to describe this type of cross-species inheritance. Introgression refers to the process by which outside genetic material is absorbed into the human genome, while adaptive refers to the evolutionary advantage humans gain from possessing such material.

This new AI program is uniquely suited for identifying instances of adaptive introgression. In the years ahead, it may dramatically expand our knowledge about the relationships that were formed between ancient Homo sapiens (modern humans) and their nearest living relatives.

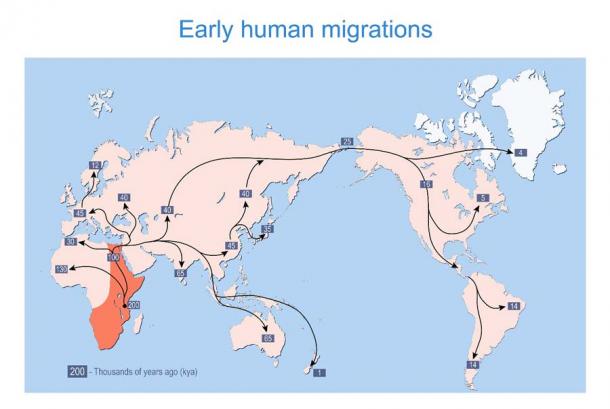

Early human migrations from Africa and onwards across planet Earth, measured in thousands of years ago (kya), included Homo sapiens, Neanderthals and Denisovans. And now we know the modern human genome, as a result of hominin species interbreeding, has a lot of genetic material from Neanderthals. ( designua / Adobe Stock)

The Human Genome: Early Human Migrations and Interbreeding

When humans migrated from Africa to Europe, Asia, and beyond more than 60,000 years ago, they met the Neanderthals, who were already living in those areas. Moving eastward they eventually encountered the mysterious Denisovans, who resided in what is now southern and eastern Asia and in Oceania (Australia, New Zealand, and the nearby islands of Melanesia, Polynesia, and Micronesia).

While these were separate species, they were closely related to Homo sapiens , close enough to make interbreeding possible. Neanderthals and Denisovans went extinct tens of thousands of years ago, but at least some of their genetic material has survived inside human DNA because of the interactions that took place in prehistoric times.

Only a few traces of Denisovan DNA are likely to be found in the collective human gene pool. But scientists believe that up to 40 percent of Neanderthal DNA may have survived inside the genomes of humans. It is widely spread out, meaning that Neanderthal DNA makes up no more than two percent of any individual’s total genetic material.

An image of the DNA helix that hints at the powers of AI or deep learning methods in learning more about the evolution of the human genome. ( Siarhei / Adobe Stock)

Deep Learning AI Insights Into the Human Genome

Those 40 percent and two percent figures are estimates, not precise measurements. Scientists don’t know for certain exactly how much Neanderthal or Denisovan DNA human beings have inherited, or how it might be distributed ethnically or geographically. They also aren’t sure where all of it is located inside the human genome. Most importantly, they still aren’t sure which functions it performs. These are the issues the GLOBE Institute scientists are trying to remedy.

“We developed a deep learning method called ‘genomatnn’ that jointly models introgression, which is the transfer of genetic information between species, and natural selection,” Fernando Racimo, a GeoGenetics Centre geneticist and the co-author of the eLife paper, told the author of a University of Copenhagen article about this new study. “The model was developed in order to identify regions in the human genome where this introgression could have happened.”

“Deep learning” is a general form of artificial intelligence (AI). The specific form of AI applied in this case is known as a convolutional neural network (CNN), which is a type of deep learning program used for image recognition .

In this experiment, the researchers ran hundreds of thousands of simulations as a way to teach the CNN to identify patterns in genomes that would be created by adaptive introgression. The AI network was specially trained to spot mutations traceable to interactions with Neanderthals or Denisovans.

“Our method is highly accurate and outcompetes previous approaches in power,” Racimo said. “We applied it to various human genomic datasets and found several candidate beneficial gene variants that were introduced into the human gene pool.”

DNA sequences in colored letters on a black background containing the word “mutation.” Based on the recent AI study of the human genome at the University of Copenhagen, researchers are now focusing on mutations more and more to understand the evolution of the modern human genome. ( Catalin / Adobe Stock)

Twists and Turns in Our Genetic Roadmap

So far, some of what the scientists have discovered confirms existing theories about where Neanderthal DNA could be found. But in the process they uncovered some new and surprising information as well.

“We recovered previously identified candidates for adaptive introgression in modern humans, as well as several candidates which have not previously been described,” said GeoGenetics Centre researcher Graham Gower, the lead author of the eLife article.

Some of the newly discovered candidates involve mutations that impact human metabolism and immunity system functioning.

“In European genomes, we found two strong candidates for adaptive introgression from Neanderthals in regions of the genome that affect phenotypes related to blood, including blood cell counts,” Gower explained. “In Melanesian genomes, we found candidate variants introgressed from Denisovans that potentially affected a wide range of traits, such as blood-related diseases, tumor suppression, skin development, metabolism, and various neurological diseases.”

Gower is quick to point out that these are preliminary findings. As of now, the scientists aren’t completely sure what impact these mutations might have on those who carry them. They might cause positive responses, negative outcomes, or have no significant effect at all.

In general, scientists assume that when mutations last for tens of thousands of years, they will do so because they are in some way beneficial. Humans who interbred with their archaic cousins likely improved the gene pool overall, adding new genetic material from species that had been surviving in environments that were relatively new to African-born Homo sapiens .

A Neanderthal skull (left) next to a Homo sapiens skull. Though the skulls are very different, it turns out that the modern human genome is almost 40% related to interbreeding and mutations related to Neanderthals. ( procy_ab / Adobe Stock)

Finding Prehistoric Facts with Future Technologies

As their study continues, the University of Copenhagen researchers hope to learn more about the actual effects of the mutations they’ve found (and those they’ve yet to find, but soon will) in the human genome.

Also, they plan to work backward from the mutations to trace the histories of the ancient people who introduced them into the gene pool. By studying which mutations developed in which population groups, they may be able to determine where Neanderthal, Denisovan, and Homo sapiens interactions occurred in the distant past, and where they were the most extensive.

This type of knowledge will give anthropologists, evolutionary biologists, and archaeologists a better idea about where fossilized remains of various species might be found, along with any artifacts they might have created and left behind.

Top image: A drawing of a Neanderthal man looking to the horizon and wondering if he will meet another “human” and, if so a human woman. The human genome it turns out has a lot of Neanderthal genes and now a Danish AI program is proving it. Source: ginettigino / Adobe Stock

By Nathan Falde

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

June 19th, 2021

June 19th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: