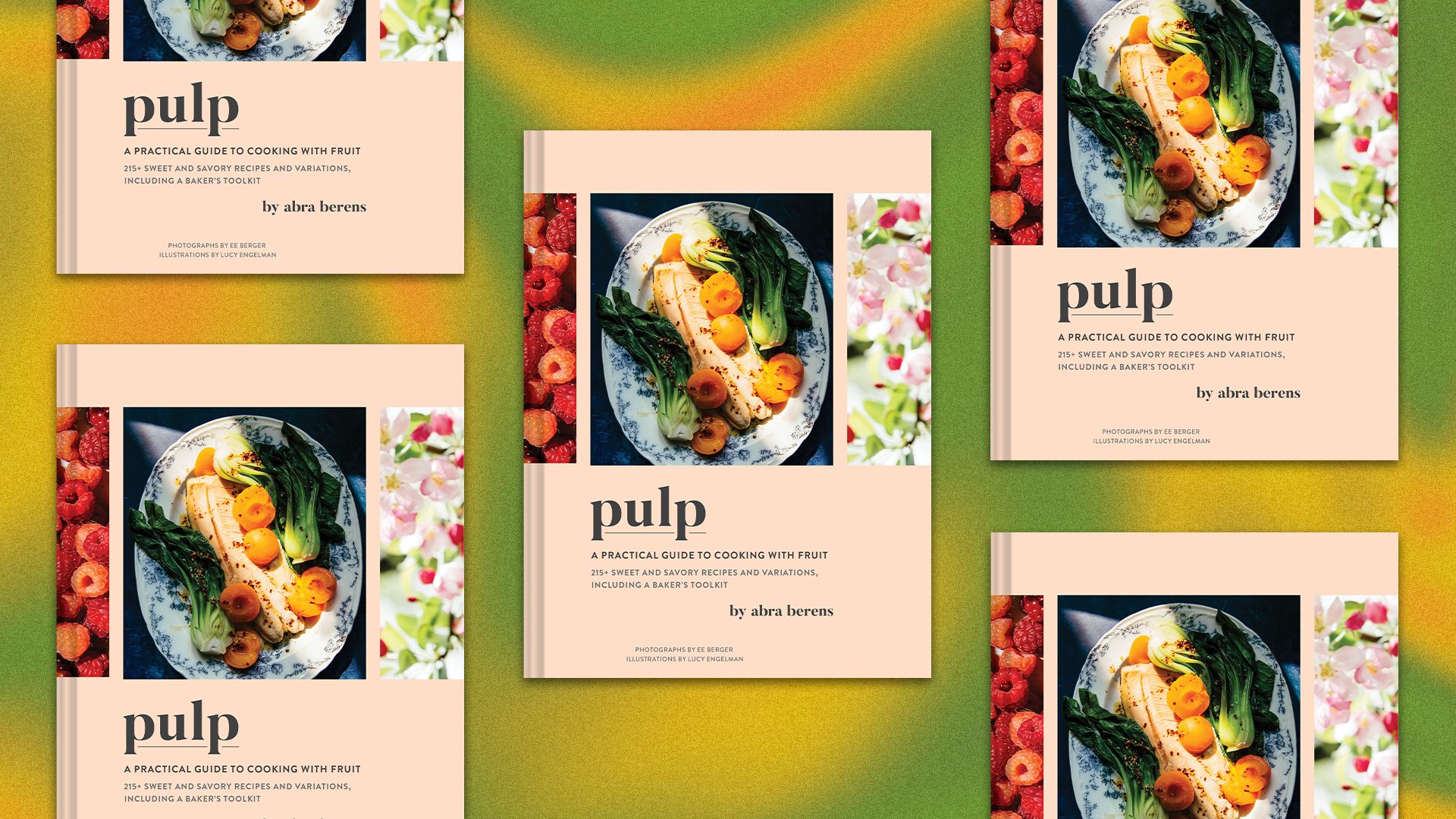

I meet Abra Berens on the release day of her newest cookbook, Pulp, which is an encyclopedic ode to all things fruit. She’s doing a book signing at Hopewell Brewing Co. in Chicago, and for the occasion, the brewery has released a special piquette-style sour ale called Neonette: Peach, which uses fermented Red Haven peaches sourced from Michigan. Berens is signing books and talking to fans; but unlike most meet-and-greets, each conversation is like five minutes long, and her signature in some of the books follows an almost paragraph-long personalized message she’ll write. Within a few minutes of my meeting her, she 1) tells me to come visit her farm in Michigan, 2) asks me to send her pictures from an upcoming dinner party where we’ll be cooking out of Pulp, and 3) offers me food she’s made for the occasion, which includes “brined cherries, olives, and salty snacks,” fresh baked focaccia, oat cakes, and an insanely good apple cranberry crumble with whipped tahini. She immediately feels like somebody I’ve known for a long time. This [gestures to everything] is the Midwest.

I include this anecdote to show that Berens really walks it like she talks it—her books are about creating harmony with your environment and finding ways to nourish yourself and others, and that’s exactly what it’s like to meet her. In her two previous books, Ruffage and Grist, she offered thorough guides on how to use vegetables, grains, beans, seeds, and legumes in your cooking. In Pulp, she enters the kingdom of fruit, closing the loop and finishing off some kind of trilogy that, when taken together, should teach us basically all we’d need to know about selecting, preserving, and cooking most types of produce.

There’s a difference between knowing how to write good recipes and being able to teach someone how to do nearly anything with food, and these books fall into the latter category. Thus, if you pick up this book (and remember it during times of abundance), rare will be the days you’ll have to toss a bag of grapes, a grip of apples, or a bunch of strawberries because they sat too long while you were paralyzed with indecision about what to do with them. This is probably a point that many reviews of this book will make, but it’s an important one.

Berens told me that her publisher was initially unsure that doing a whole book about cooking with fruit was a good idea, but for her, nothing would seem more obvious—she writes in the book’s introduction that fruit is inextricable from her cooking. “It’s possible there is so much fruit in my cooking because I’m from Michigan,” she explains. “The mitten state is the second-most agriculturally diverse state in the union, due in large part to the tremendous amount of fruit we grow.” She makes an extremely compelling argument that we should all be cooking with fruit, even if we aren’t living in Michigan or another fruit-bountiful area (though you can bet your ass I’ll be crossing state lines to get buckets of blueberries and peaches this summer). “When life gives you lemons, make lemonade, sure, but also lemon squares, preserved lemons, grilled lemon relish, and lemon curd,” she implores. “Fruit lends acidity, sweetness, color, and a range of different textures to dishes both sweet and savory.”

To that effect, this cookbook isn’t a compendium of cakes, ice creams, and cobbers—not at all. Well, it is, but for every sweet dessert, there’s a savory counterpart. The book is smartly broken up by fruit, and within each chapter, readers are offered numerous appropriate ways to handle them. Options include: raw, grilled, roasted, poached, baked, preserved, stewed, poached, and beyond. If you find yourself with way too many cherries, just flip to that chapter and you’ll find ways to serve them raw, bake them, grill or roast them, and preserve them. Feel like a whole cherry-centric menu? Start off with some cherry baked brie with seedy crackers; then, try an entrée of buttermilk pork tenderloin with grilled cherry salad; and finish with chocolate pudding with coffee-soaked black cherries. Literally while writing this paragraph, I got an email from a producer I really like, Frog Hollow Farm, with the subject line: “Lock in Your Cherry Season—Harvesting Soon!” We’re all connected, my brothers and sisters in produce. Just listen to the signs.

We need to learn how to be more sustainable in the buying and using of our produce. If you’ve ever thrown away stuff from your fridge because it went bad, Ruffage, Grist, and Pulp are for you. In that sense, Pulp isn’t just a fruit cookbook—it’s also a love letter and a call to arms. The book is punctuated by producer profiles, and offers valuable commentary on the fruit industry, the economics of fruit, and terms like “local” and “seasonal.” “I find vapid discussion glorifying food while ignoring the people who grow or process our food very, ahem, frustrating. It is trite but true: no farms = no food,” Berens writes. “We have to go beyond a superficial rah-rah-rah for growers.” This is, unfortunately, a formulation we’ve also heard in recent years about teachers, nurses, and service workers—the people who labor hard to maintain the structures of our daily lives, and are severely undervalued for it.

Another winner from Berens, Pulp is a beautiful and necessary book for anybody who loves fruit and wants to not only find good recipes, but wants to really learn how to handle it and use it in the most efficient and delicious ways possible. An avid cook and regular fruit smoothie and juice enjoyer, I always have a ton of blueberries, bananas, apples, strawberries, lemons, and more sitting around the house. It’s embarrassing how few of their possibilities I explore. Pulp gives me the motivation and tools to make the most of my fruit, and takes away my excuses not to. If I don’t use it, that’s on me. It’s true for all of us.

The Rec Room staff independently selected all of the stuff featured in this story. Want more reviews, recommendations, and red-hot deals? Sign up for our newsletter.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

April 8th, 2023

April 8th, 2023  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: