They were were taken from their homes and sent to work on cotton farms and sugar plantations, cattle farms and sheep stations, were there were no limits on how many hours they worked, how hard was the labor, how bad was the treatment or the provision of food and living quarters. Sound familiar? But these slaves, deprived of all personal freedom, were Aboriginal Australian slaves, and their history has been scrubbed from textbooks.

The history of Aboriginal slavery has long been suppressed, and a modern movement of Australian slavery denial has even gained mainstream acceptance. Promoters of this toxic ideology simply don’t want to face up to the fact Australia has a history of genocide and slavery.

But there is no question they were slaves. If you read it up in the dictionaries, slavery is “the condition in which one person is owned as property by another” and the owner has “absolute power” over their “life, liberty, and fortune”. Such people are usually forced into work “in harsh conditions for low pay”.

SBS reports:

1. Just because the history books don’t call it slavery doesn’t mean it’s not slavery

Much like the words ‘invasion, ‘theft’, massacres’, and ‘wars’, Britain and Australia are uncomfortable using the word slavery in reference to their history. But no matter what you call it, the forcing of thousands upon thousands of people to work for no money, or only for basic rations, is tantamount to slavery by any meaningful definition.

Blackbirding, Stolen Wages, indentured service, indentured labour; are all words that have been used to avoid the harsh bite of the word. However, the realities of these words have always been much the same; unpaid labour, unsafe working conditions, exploitation, abuse, and decades long campaigns for justice and recognition – many of which are still ongoing. This is a significant relationship between Indigenous and white Australians.

2. The people are still alive to tell the tale

While the forced labour of Aboriginal people by the Federal and state Governments formally began in the late 19th Century, the system didn’t end until up to the 1970s. This means that there are number of people in our community today who lived through this experience. It’s a period that led to what is now known as the Stolen Wages and is intimately linked to Stolen Generations history.

3. The recent documentary Servant or Slave

“As an Aboriginal filmmaker I thought it my duty to give the generation a clear voice and audience in fear that in another twenty years or so, they might be gone, taking their stories with them”, writes Mitchell Stanley, filmmaker of Servant or Slave.

Awarded a 5-star review from the Guardian, Servant or Slave (On Demand here) tells the stories of five women who experienced Australia’s slavery system first-hand. All members of the Stolen Generations, Rita Wright, Violet West and the three Wenburg sisters, Adelaide, Valerie and Rita share their experiences of being forcibly removed from their families, put into domestic training homes as children and being sent out to work as domestic ‘help’, and life after working in unsafe conditions for no money.

“Many Australians have some knowledge, or assumption, of the kinds of things that might have transpired during these dark times. But to hear them articulated by the victims themselves, and illustrated by powerful albeit discreet re-enactments, brings the details to mind in terrible ways,” says director, Stephen McGregor.

4. The groundbreaking documentary Lousy Little Sixpence

An influential film (access here) by Alec Morgan which comprised interviews and historical never-before-seen footage tells the long history of unpaid servitude of Aboriginal people.

It was premiered in 1983 at the Sydney Film Festival and was the first media of it’s kind to discuss – reveal, even – this widespread dark history. Audiences were so affected that some viewers thought the film was fiction because the concept was too shocking to be conceived as real.

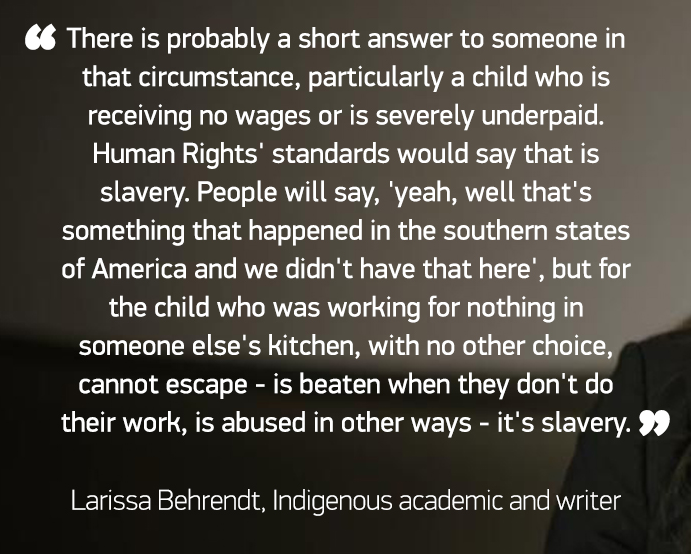

5. This quote from Larissa Behrendt

Indigenous academic and writer, Larissa Behrendt makes the point on documentary Servant or Slave:

6. Rations are not wages

In some cases, indentured labour as slavery is argued against or denied, as the people in question were often paid in rations. This is uncannily similar to those in the US who try to refuse the atrocity of their slavery period by making a point that people were fed and housed as part of the process. *Ahem*. Of course people were fed, human beings require sustenance for energy – energy that was ironically used to encourage them to work for hours on end for no pay.

7. More people know about the Stolen Generations than Aboriginal slavery

Generally, the public is not as aware of wages being stolen from Indigenous people as high as children being removed from families.

While the Bringing Them Home Report by the Australian Human Rights Commission was released in 1997 – which was courtesy of academics, artists, activists and performers such as Peter Read, Alec Morgan, Kev Carmody, Archie Roach and even Midnight Oil who increased public awareness and pushed the agenda – a Senate Inquiry into the monies stolen wasn’t held until a decade later – in 2007.

There are also significant barriers to Indigenous people finding out just how much they are owed as many records and government document have been incomplete, lost or destroyed. Some of the records were deliberately destroyed, particularly when Aboriginal Welfare Boards were disbanded in the late 1960s. It’s also important to consider that many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were not allowed bank accounts until the 1970s, so payment processing were added hurdles.

The Stolen Generations and Stolen Wages are not mutually exclusive. Many members of the Stolen Generations later had their wages withheld while working as domestics or farm hands after ‘completing’ their training in the homes that they were taken to after being forcibly removed from their families. Stolen Generations were stolen and thrust into the Stolen Wages system.

8. Australia’s slavery started because other countries abolished it

Britain wanted cheaper cotton, but the world’s cotton market had been thrown into turmoil because the UK abolished slavery in 1833 and mass slavery ended in the United States after the Civil War in 1865. But this didn’t stop the British from accepting it elsewhere.

Starting in the 1860s, slavery and the Aboriginal labor debate were clearly linked. Religious and humanitarian organisations used ‘chattel bondage’ and ‘slavery’ to describe north Australian conditions for Aboriginal labor, and the word was regularly used by journalists and human rights activists for another 100 years, until the 1960s.

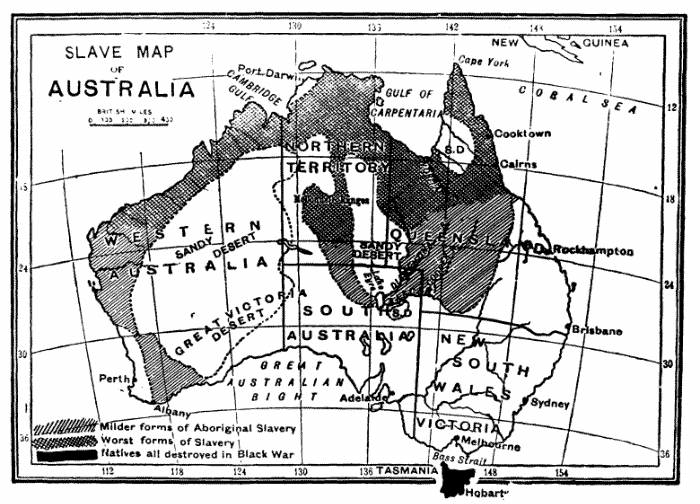

Writer Arthur James Vogan, in his 1890 novel The Black Police: A Story of Modern Australia, included a ‘Slave Map of Modern Australia’ towards the end of the novel. It was reprinted in the September-October 1891 edition of the British Anti-Slavery Reporter. It showed most of central and north Queensland, the Northern Territory and coastal Western Australia as areas where “the traffic in Aboriginal labour, both children and adults, had descended into slavery conditions”.

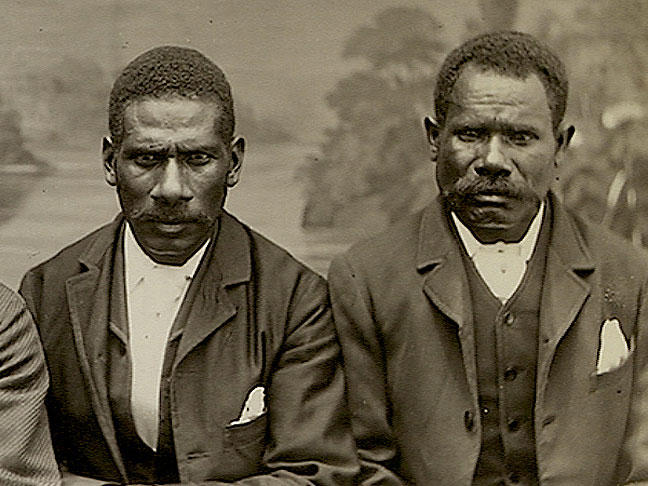

9. It didn’t only happen to Indigenous Australians

It didn’t just happen to Indigenous Australians. You should know about ‘Blackbirding’.

‘Blackbirding’, in Australia, was the practice of kidnapping or coercing Islanders from Vanuatu, the Solomon Islands, and other nearby islands to work in Australia as indentured labourers.

It is believed that over 50,000 people were brought into New South Wales and Queensland, predominantly in the 1800s. Although there were legal frameworks in place to allow this practice, it is regarded by many as having been a mere pretense to justify what would otherwise be acknowledged as criminal practices.The 1901 Pacific Island Labourers Act saw approximately 7,000 people deported, tearing families and communities apart.

An excellent article in the Sydney Morning Herald by Emelda Davis, a second generation descendant of South Sea Islanders who were blackbirded, speaks of the inhumanity and cruelty of this deportation by noting that, “the wages of 15,000 deceased Islanders were used for this deportation and the low and hard-earned wages of the Islanders were used to pay part of their fare to return to the islands that in some cases had seen their entire male population kidnapped.”

10. Indigenous slave labor is still happening

Today, there are some Indigenous people in Australia who are required to work a minimum 46 weeks a year for the Government with no leave entitlements and no superannuation, and are paid a significant portion of their wages on a card that can only be spent in certain stores and on certain wages.

Most Americans are perfectly familiar with the fact that their country was built on the backs of slavery, that their wealth has its roots in slave labor and that this history can help to explain why African-Americans still experience discrimination today.

Australians, on the other hand, are blissfully ignorant until they’re forced to confront it, at which point, they ask that it not be mentioned again. The same applies to any other uneasy chapter of Aboriginal history.

“The vast majority of non-Indigenous Australians have no idea of the enormous debt they owe to the Aboriginal men, women and children whose labour built this country,” says historian and author Dr Rosalind Kidd.

“They have no idea that many workers would have had money and freedom to prosper if governments had not stifled their choices, ignored, unpaid and underpaid [their] labour, and misused their earnings and entitlements.”

Source Article from http://yournewswire.com/aboriginal-australian-slaves/

Related posts:

Views: 2

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

April 24th, 2017

April 24th, 2017  Awake Goy

Awake Goy

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: