The Grimaldi Goddess clay figurine, unearthed at the Neolithic settlement of Çatal Hüyük in Turkey, dates back to about 6000 BC. It depicts an obese woman giving birth while seated upon a throne. Although many have considered this a sure sign of feminine fertility, many scholars have dismissed the two massive dog-like beasts sitting by her side. The focus has continued being about sexual reproduction symbols, rather than her role in dog domestication and dominance over woman’s best and most loyal friend.

While historians and archaeologists have debated the controversial issue of gender within the division of labor, the role of women in the rearing and domestication of animals has mainly been credited to men. The academic community has assumed that dogs were used for assistance in hunting and herding, due to the influence of men. But can the story of domestication be that simple, especially when every region of the world has had a different experience when it comes to human survival?

The role of women in different cultures is not universal, with significant disparities regarding gender and division of labor , so why should we assume that only men were responsible for domestication? A closer look reveals that some of the oldest goddesses in human history have strong associations with the worship and rearing of dogs. Meanwhile, in the northern hemisphere, before the arrival of the Spanish and their horses, folklore and century-old ethnographies of the Blackfoot and Pawnee Plains Indians include accounts of American wolf/dog hybrids trained by women to haul supplies on travois for the sake of hunters.

While we will never know the specific part played by women in the domestication of dogs across different cultures, the author of this article believes that women played a larger role than most would like to admit. Could this potentially mean that women were the first to domesticate man’s best friend?

The Grimaldi Goddess clay figurine, unearthed at the Neolithic settlement of Çatal Hüyük in Turkey, dates back to about 6000 BC and depicts a seated woman of Çatalhöyük. The author argues that the two massive dog-like beasts sitting by her side could hide secrets related to the role of women in dog domestication. It is housed at the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara, Turkey. ( Nevit Dilmen / CC BY-SA 3.0 )

On Becoming Man’s Best Friend

Throughout most of human history, our ancestors were subject to the laws of nature, no different from any other animal. On the one hand, the moment our human ancestors learned to harness fire changed the course of our survival. On the other, the moment that humans domesticated the wolf altered the course of the entire world. It will forever remain a mystery as to whether humans tamed wolves after capturing them and imposing respect, or whether wolves tamed themselves due to curiosity and their impetus to scavenge. The result however was an unbreakable union between two apex predator species.

Many scientists have suggested that the domestication of the ancestor of the grey wolf began between 38,000 to 10,000 years ago, either in Europe, the Middle East or Asia. This one event enabled humans to begin shaping their environment and to understand the animals around them. Humans now had a companion species doubling their chances of survival, protection, and luck during hunting with dogs. It also potentially gave humans the ability to carry supplies over long distances, as has been evidenced in many cultures in the northern hemisphere up until the early 19th century.

The process of wolf domestication would have been no different than the soviet experiments performed by Dmitri Belyaev related to the domestication of wild foxes. Wolf cubs that were aggressive would have been killed or given away, while the complacent and friendly were kept and encouraged. Shortly after, came the rise of agriculture, leading humans to begin adopting a more sedentary way of life. This brought with it further gender division of labor and skills. The conventional belief is that men took to the fields, hunted and were responsible for the domestication of animals, while women made pots, ceramics, textiles, and children. The earliest evidence of dog domestication appeared in Turkey, Syria, and Israel alongside wild grain. Other sites such as ‘Ain Mallaha in Syria revealed the ruins of ancient dwellings and storage pits, as well as the burial of humans with their dogs dated to about 8,000 BC.

It would appear logical and sound if one were to remain under the classical western school of thought. But alas, nothing in science, culture, or nature is ever that simple, and many assumptions have been made when discussing gender and the division of labor. The archaeological record has uncovered some interesting alternatives when considering the link between women and dog domestication.

In northern Israel, archaeologists discovered the remains of a 12,000-year-old Natufian woman with her hand resting on a pet puppy, at the ‘Ain Mallaha site. This is one of the first known remains related to dog domestication. ( The Israel Museum, Jerusalem )

Burial Sites: An Eternal Bond Between Women and Their Dogs

Around the world, several archaeological sites reflect the alliance between humans and dogs. These include burials which reveal the undying bond between women and their canine friends. Most of these sites range anywhere between 12,000 to 8,000 years old. Within the remains of more recent settlements, ranging between 10,000 and 5,000 years old, the burials discovered reveal an increasing amount of men being buried with their dogs. This growing commonality may allude to changing beliefs and gender expectations as societies became more structured.

As the scholar Callahan notes, at the ‘Ain Mallaha site in northern Israel, the excavation of a 12,000-year-old Natufian burial exposed the skeleton of a woman with a puppy’s remains near her head. On the other side of the world, at the excavation site Danger Cave in Utah, evidence of some of the oldest bonds between dogs and humans in North America have been recovered. One of these is the finding of the remains of a small terrier-sized dog buried with a woman. At the same site, a man was also found alongside the remains of a larger dog. Danger Cave could be evidence of specific dog types being designated according to gender.

At an excavation site near Lake Baikal in Siberia, the archaeologist and geneticist Andrea Waters Rist from Leiden University discovered two 8,000-year-old skeletal remains of Neolithic Siberian women carrying signs of the parasitic infection known as echinococcosis. This disease occurs when humans have long interaction and contact with canines through the sharing of food, water, and in some instances from being exposed to canine fecal matter. Waters-Rist’s analysis concludes that ancient Siberian women of this forgotten tribe might have been responsible for the caring, feeding, and rearing of dogs.

Within every culture, there is distinct evidence that women were significant to the rearing and training of dogs. Shortly after the domestication of the dog, humans lived side by side with these animals, considered them equals, and depended on them for protection and assistance in their everyday lives. According to scholars such as Waters-Rist, it is therefore not surprising that humans would also endure the same sicknesses as well.

As time went on, dogs were reared by both men and women, and they eventually became part of the family unit across many cultures. Without the friendship and alliance of dogs, there would be no human civilization. This fact must have been well understood in the ancient world, as there are several goddesses associated with dogs. Could these dog-friendly deities provide clues to the relationship between women and dogs?

Painting by Jacob Jordaens showing the Greek goddess Atalanta, who is often painted equipped with a bow, spear, and dogs. ( Public domain )

Dog-Friendly Deities: Women and Dogs in Mythology

Aside from the Grimaldi Goddess figurine hypothesis previously mentioned, the list of gods who demonstrate a strong relationship with dogs include the goddess Gula, also known as Bau, Nintinugga, and Basat, who was often represented sitting near dogs. The goddess of dogs and healing, in her earliest form she was described as the dogs’ controller, but she became associated with spells and healing in later years. Her temples were prevalent in Mesopotamia, Babylonia and Sumer, and stray dogs were allowed to roam within their walls. Altars at her temples were littered with dog statues, dedicated to her in the hope she would provide speedy recovery for loved ones. Her sacred symbol remained that of the dog until she was forgotten over time.

Left; Detail of the goddess Nintinugga, her dog, and a scorpion man from kudurru of Nebuchadnezzar granting Šitti-Marduk freedom from taxation. British Museum. ( CC BY-SA 4.0 ). Right Public Domain )

Other powerful mythical deities and goddesses were associated with hunting. The goddess Atalanta was often painted equipped with a bow, spear, and dogs, not to mention a severed boar head, representing luck with the hunt and fruitful prosperity. As the scholar Adrienne Mayor has mentioned, vase paintings depicted Amazon archers accompanied by dogs as they ran to battle or hunted. The eternal bond between women and dogs, especially on Greek vases, is evidence of an unbreakable connection. The goddess Artemis (Diana) is another deity which illustrates the connection between women, hunting and a feminine command over dogs, wolves, and animals. Another Greek goddess was Hecate, who was responsible for crossroads and entryways, as well as dogs. However, her depiction was far more sinister, as she represented the unpredictability of magic and spells. She was a shapeshifter, described as having three heads and was often responsible for dog barking, since they were obliged to announce her entrance anywhere she went.

Amongst the ancient Greeks, there are a few common themes related to women and dogs, in that their companionship was seen as old and mysterious, but beneficial for all. Much ancient Greek art portrays men hunting with hounds, but the representation of warrior women and ancient hunting deities could help shine a light on a past when women trained dogs for hunting and gathering.

There is not much evidence to speak for this hypothesis, besides some Greco-Roman art and a few Scythian warrior women gravesites with hounds. There is however significant evidence of women rearing and training dogs for the purpose of assisting in hunting and carrying supplies. The most extraordinary evidence can be seen with the ethnographic accounts of early North American Plains Indians as they spoke of the time before the arrival of Spanish horses.

There is significant evidence of women rearing and training dogs in ancient history to assist in hunting and carrying supplies. ( Public domain )

Cultural Power of the Dog: Dog Domestication Amongst the Plains Indians

North American archaeologists have argued that the domestication of dogs may have been a significant reason for why the early peopling of North America took place. Along with many other theories suggesting a long and staggering land migration, and even by way of ancient boats following the kelp trail, using dogs as beasts of labor may have aided in the transport of essential tools and supplies. In the New World, many scholars credit the partnership of humans and dogs as a significant factor in the extinction of the American megafauna . With the aid of dogs as hunters and pack animals, humans were able to outmaneuver their prey and bring back a significantly larger portion of their kill.

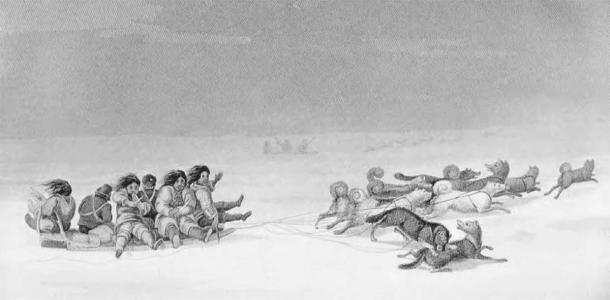

In studies of the Plains Indian cultures, such as the Cree, Blackfoot, and the Pawnee, many scholars, including Driver, Massey, Brasser, Welker and Byers, have dated the creation of the travois (a type of sled) in the northeastern American plains as early as 900 AD. Even though the archaeological evidence may be limited, there have been several ethnographic accounts within their myths and stories discussing what hunting was like before the incorporation of European horses, an event which completely altered their way of life and hunting methods.

Even later, when horses eclipsed the dog as the primary source of animal labor, the dog’s cultural power remained prevalent amongst the Plains Indian cultures, as this 1730 account from the elder Cree Saukamapee notes:

“…As the leaves fell, they heard of a horse that was killed by an arrow shot into his belly. The Blackfeet gathered around the dead animal, trying to make sense of the singular encounter— we admired him… We did not know what name to give him. But as he was a slave to Man, like the dog, which carried our things; he was named the Big Dog” (Saukamapee 1730).

Similarly, within the other languages of the Plains Indians, the horse was called “big dog” by the Blackfoot and Cree, “great dog” by the Assiniboine, “seven dogs” by the Sarcee, and “medicine-dog” by the Lakota (Hamalainen, 2003). With the names given to the horse, it was apparent that the dog still carried significant power for most of the Plains Indians. Despite the increasing dependence on horses ever since their introduction, they continued to rely on dogs, especially the women.

The Plains Indians utilized dogs for hunting, transporting of goods, and, in the most extreme of occasions, as food. Their jobs pertained to hauling meat, tent poles, firewood, water sacks, and personal items when needed. It was very common to have dogs with saddlebags or tied to a travois carriage whenever it was necessary.

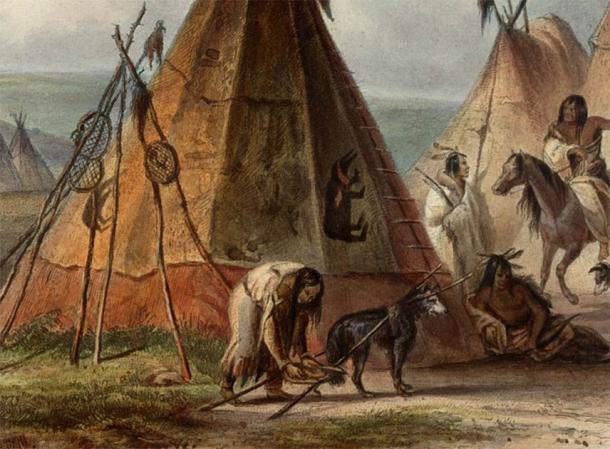

Detail from a Karl Bodmer painting showing a dog with a travois in an Assiniboine camp in the Great Plains. ( Public domain )

Women and Dogs in North American Plains Indian Culture

The most famous account is from the Hidatsa elder Buffalo Bird Woman. In her stories from the past, she discusses the older way of life for women and dogs within the American Plains culture. Her account explains that even after incorporating horses, it was only the more affluent families that could afford to house them. Most families still relied heavily on dog transportation by way of travois, two-pole sleds used by North American Plains Indians to carry goods, and their brutal nomadic way of life.

She states that women were considered the owners of dogs. They were expected to raise them, clean them, and train them. Like in many other cultures, the methods for domesticating dogs revealed a selection process over generations favoring the more complacent over the vicious and mercurial. The most favorable of puppies had large round faces, big legs, and floppy ears. These traits revealed a loyal and happy dog that would grow up big. Puppies that did not meet these criteria were often killed or given away.

Her narrative involves women training the dogs in hauling weights, in order to get an adult canine ready and able to carry between 50 and 70 pounds (22 to 32 kilos) by travois. Once this task was completed, the dog would be used for multiple purposes. In some situations, anywhere from 20 to 70 dogs would be brought on hunts and expected to carry the processed buffalo meat back to camp without being tempted to eat any of it. Women would also take packs of between 12 and 20 dogs to collect firewood and supplies to sustain their families one month at a time. With every task given, it was still customary for a woman to care and equip the dogs, as well as ensure they were comfortable in their tasks.

According to Buffalo Bird Woman’s account, dogs would always follow in single file behind their women owners, and if any of the dogs tired, the women would know how to keep them encouraged. In the summer, women knew not to load dogs as heavily as in winter. This had to do with the heat and the friction from the ground. During winter, the weather and snow worked in a travois-pulling dog’s favor. It was also necessary for women to continue keeping the dogs hydrated throughout the day, for they were always in use.

As time went on, the horse replaced the dog in their society, and further technological advancements eventually replaced the horse as well. These changes beg questions of how indigenous people lived before the arrival of Europeans, and whether the role of women in the care and training of dogs was a recent tradition, or if it had occurred for thousands of years. Our only source of information is the account from Buffalo Bird Woman and her discussion of the saddlebag and travois dogs.

It’s important to stress that the opinions contained in this article are solely a working hypothesis by the author and intended to raise questions regarding the historic relationship between dogs and women. Though the evidence used is limited to a few burial sites, cultural references to early goddesses associated with dogs, and a long tradition of women caring and training dogs within the North American Plains culture, the question is still up for debate. What makes it even harder to answer is the archaeological dogma that has assumed men and women’s roles throughout prehistory. Without losing site of the limitations of this analysis, it remains interesting to analyze the relationship between women and dogs, and the role they may have played in dog domestication, in the hope of someday finding answers.

Top image: Could it be that women throughout history have been responsible for dog domestication? In the image we can see Diana in a 20 th century tapestry by Renato Torres. Source: TapestryDiana / CC BY-SA 4.0

By B.B. Wagner

References

Bozell, John R., 1988. “Changes in the Role of the Dog in Protohistoric-Historic Pawnee Culture.” Plains Anthropologist (Taylor and Francis, Ltd. On behalf of the Plains Anthropological Society) 33 (119): 95-111.

Callahan, Ruth. 1997. “Domestication of Dogs and Their Use on the Great Plains.” Nebraska Anthropologist 1-12.

Clark, Mike. n.d. 5 Canine Gods and Goddesses Your Dog Could Be Related To. Available at: https://dogtime.com/reference/27040-canine-gods-goddesses

Fiedel, Stuart J. 3005. “Man’s Best Freind — Mammoth’s Worst Enemy? A Speculative Essay on the Role of Dogs in Paleoindian Colonization and Megafaunal Extinction.” World Archaeology 37 (1): 11-25.

Hamalainen, Pekka. 2003. “The Rise and Fall of Plains Indian Horse Cultures.” Journal of American History 832-862.

Handwerk, Brian. 15 August 2018. “How Accurate is Alpha’s Theory of Dog Domestication?” In Smithsonian Magazine . Available at: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/how-wolves-really-became-dogs-180970014/

Hare, Brian, and Vanessa Woods. 3 March 2013. “Opinion: We Didn’t domesticate Dogs. They Domesticated Us” in National Geographic . Available at: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2013/3/130302-dog-domestic-evolution-science-wolf-wolves-human/

Henderson, Norman. 1994. “Replicating Dog Travois travel on the Northern Plains.” Plains Anthropologist (Taylor and Francis, Ltd. On behalf of the Plains Anthropological Society) 39 (148): 145-159.

Mayor, Andrienne. 2014. The Amazons lives and Legends of Warrior Women Across The Ancient World . Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Milliken, Grennan. 19 October 2015. “The First Dogs may have been Domesticated in Mongolia” in Popular Science . Available at: https://www.popsci.com/dogs-may-have-been-first-domesticated-in-central-asia/

Perri, Angela, Chris Widga, Dennis Lawler, Terrance Martin, Thomas Loebel, Kenneth Farnsworth, Luci Kohn, and Brent Buenger. 2019. “New Evidence of the Earliest Domestic Dogs in the Americas” in American Antiquity (Society For American Archaeology) 84 (1): 68-87.

Peterson, Jane. 2010. “Domesticating Gender: Neolithic Patterns from the Southern Levant” in Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 249-264.

Robertson, Lindsay. 18 July 2014. “Cave women were just like Us: They May have Domesticated Prehistoric Dogs” in The Dodo. Available at: https://www.thedodo.com/cave-women-were-just-like-us-t-633637134.html

Sassamen, Kenneth E. 1992. “Lithic Technology and the Hunter-Gatherer Sexual Division of Labor.” North American Archaeologist 1-16.

Tarlach, Gemma. 8 November 2016. “The Origins of Dogs” in Discover Magazine . Available at: https://www.discovermagazine.com/planet-earth/the-origins-of-dogs

Viegas, Jen. 18 July 2014. “Dogs were a prehistorica Woman’s Best Friend, too” in Seeker. Available at: https://www.seeker.com/dogs-were-a-prehistoric-womans-best-friend-too-1768822014.html

Waters-Rist, Andrea L, Kathleen’ Lieverse, Angela’ Bazaliiski, Vladimir Faccia, M.Anne Katzenberg, and Robert J Losey. 2014. “Multicomponent analysis of a hydrated cyst from an Early Neolithic hunter-fisher-gatherer from Lake Baikal, Siberia” in Journal of Archaeological Science 50: 51-62.

Wayland Berber, Elizabeth. 1994. Women’s Work: The First 20,000 Years . New York: W.W. Norton and Company.

Welker, Martin H, and David A Byers. 2019. “The Birch Creek Canids and Dogs as Transport Labor in the Intermountain West” in American Antiquity (Society for American Anthropology) 84 (1): 88-106.

Yong, Ed. 2 June 2016. A New Origin Story for Dogs . Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2016/06/the-origin-of-dogs/484976/

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

October 4th, 2020

October 4th, 2020  Awake Goy

Awake Goy

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: