I became an American citizen this week. Over the past nine and a half years, first there were visas, then there were green cards, and finally, this week, we were upgraded to citizenship.

I told a few people about it on the day it happened, and they all wished me “Mazel tov!” What struck me is that there doesn’t seem to be a formal congratulatory greeting for citizenship. And I couldn’t help thinking: why not? After all, becoming a citizen of the United States is hardly an easy process, and getting to the finish line is surely worthy of its own formal phrase of acknowledgement.

We spent the last few evenings before the immigration interview intensely studying and reviewing our civics general knowledge, until we felt confident that our knowledge of US Constitutional history and related information was robust enough to face the grilling we expected. Well, it didn’t turn out to be the interrogation that online guide sites suggested it might be.

The immigration officer assigned to me (all of us were separated for individual interviews) asked me who the first US president was and what the ‘rule of law’ means, and another couple of questions that were easy to answer, and then seemed more interested in how it has been for me as a rabbi ministering to those in need during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Related coverage

March 12, 2021 12:48 pm

I told him that I wake up every morning feeling incredibly lucky, and that the first thing I say each day is “thank you Hashem” for everything I have. “Who is Hashem?” he wanted to know. I smiled, and told him that us Jews don’t say God’s name in Hebrew unless we are engaged in formal prayer; instead we say “Hashem” — which in Hebrew means “the name.”

The immigration officer found this fascinating, and made a point of writing “Hashem” in his notepad. “From now on, I’m going to wake up every morning and say ‘thank you Hashem,’” he told me. “You taught me something very important — however hard we have it, here in the United States we are so very lucky, and we definitely need to thank Hashem every day, even several times a day.”

I nodded in agreement, as he printed off my citizenship approval and told me that the swearing-in ceremony was the next day at 3pm.

We arrived the following afternoon with just minutes to spare. Due to the COVID-19 restrictions, the mass two-hour swearing-in ceremonies have currently been abandoned in favor of mini-ceremonies of about a dozen people that last only a few minutes. After picking up our citizenship certificates, we were all asked to raise our right hands together, and swear an oath of allegiance to the United States.

“I hereby declare on oath that I absolutely and entirely renounce and abjure all allegiance and fidelity to any foreign prince, potentate, state, or sovereignty, of whom or which I have heretofore been a subject or citizen…” — no small statement for a subject of Her Majesty the Queen, although perhaps made somewhat easier in a week when the royal brand took quite a beating, after the Duke and Duchess of Sussex gave their rather shocking interview to Oprah Winfrey.

“… that I will support and defend the Constitution and laws of the United States of America against all enemies, foreign and domestic…” — well that’s hardly a problem; as a strong believer in the carefully calibrated republican democracy of the United States, I felt very good bellowing out those words at the top of my voice.

“… that I will bear arms on behalf of the United States when required by the law…” — truthfully, I’m not sure what use I could ever be to the United States military, unless they need a Daf Yomi shiur or some rousing words of religious encouragement. Bearing arms seemed to me like a bit of a stretch. But hey, I’m totally ready if they really need me.

“… that I will perform noncombatant service in the Armed Forces of the United States when required by the law; that I will perform work of national importance under civilian direction when required by the law…” — Okay, now we’re talking. That sounded more like me.

“… and that I take this obligation freely, without any mental reservation or purpose of evasion; so help me God.” As I said those words, I was thinking of the immigration officer I’d inspired the day before, and I wanted to change the word ‘God’ to ‘Hashem’ — although I didn’t. But to top it all off, I did add “Amen” at the end of the oath, and started clapping. Everyone clapped along, and we all smiled, delighted. The deed was done.

What a moment. Off we all went separately to celebrate, and now we’re all Americans, able to lead our lives in this wonderful country.

I was very taken by the necessity of swearing allegiance together with a group of people I’ve never met, and in a way, I was sorry that COVID-19 had prevented me from doing it alongside hundreds of new citizens in a mass ceremony, which spoke to me about this week’s parsha.

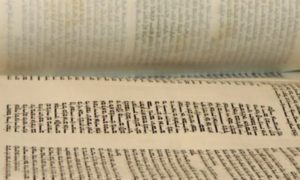

The opening verses of Vayakhel seem quite awkward. The portion is predominantly occupied with the instructions for building a temporary sanctuary for God’s presence, known as the Mishkan, but the opening verses deal with the restrictions of Shabbat. And yet, despite dealing with restrictions, the verse uses the phrase la’asot otam: “to do them.”

There is no other place in the Torah where the nation is referred to as kahal, a “community.” In which case, why is it specifically the instructions regarding Shabbat restrictions that use this collective noun?

The Midrash informs us that it was at this particular moment that Moses instituted a requirement for communal study every Shabbat. It is this requirement for a shared learning experience which contains a powerful lesson that explains the use of both la’asot otam and kahal.

The effect of any mitzvah is primarily on the individual who does it, and the mitzvah has a negligible impact on the community-at-large. For example, if one person keeps a kosher home, this won’t impact the community’s observance of the dietary laws. The reverse is also true — namely, if a community observes kosher laws, this won’t necessarily affect what an individual within that community does at home.

Shabbat is the exception to this rule. If an individual observes Shabbat surrounded by others who don’t observe Shabbat, their experience will be very different than the experience of someone who observes Shabbat amidst a community that also does Shabbat. And there’s more — it is through each individual’s Shabbat observance that an environment of Shabbat is created that enhances the community’s Shabbat experience.

And that is why the verse refers to kahal — a community, and why it states la’asot otam — because by observing the restrictions of Shabbat, each individual is coming together as a community to ‘do’ and ‘create’ a collective Shabbat experience.

American citizenship is not a selfish, individual experience, in which individuals express individual beliefs and hope that others will do so as well. Only if every American citizen pulls together to become part of a wider American ‘community’ will the dreams of America’s founding fathers properly come to fruition. Recently, and most sadly, we have seen these ideals put severely to the test — and the challenges we face on this front are far from over.

The experience of raising my hand alongside others this week in a collective declaration of fealty to the American system is exactly what makes this country so great. Those who undermine that collective consciousness — even if they are doing so for the most principled of reasons — might potentially cause repercussions which will destroy everything that has been built up over the past almost 250 years.

Let us pray that it never happens. And to that, I think we can all add “Amen.”

The author is a rabbi in Beverly Hills, California.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

March 13th, 2021

March 13th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: