Born in Florence in the late thirteenth century, Dante Alighieri would grow up to become one of the most famed and well-read authors of the Italian Middle Ages. The scope of his political and philosophical intellect would serve him well in his best-known work, The Divine Comedy, in both its depth and the nature of its allusions. This book became highly valued among scholars long after his death, yet many long years of personal struggle and emotional turmoil led to its creation. Before Dante Alighieri reached his own Paradise, he certainly went through his own personal versions of Purgatory and Hell.

Dante’s Early Life

Due to an astrological reference within The Divine Comedy , it is widely believed that Dante was born in 1265 sometime between mid-May and mid-June. Scholars further believe that, as a youth Dante and the rest of the Alighieri family enjoyed some level of power and prestige within the city of Florence because his father Alighiero di Bellincione served within a faction of supporters for the Holy Roman Emperor.

This faction divided into two, the Guelphs and the Ghibellines, in the century before Dante’s birth, the former in favor of the Pope while the later supported the Holy Roman Emperor. Working in such close association with the head of Catholicism, it is commonly believed that Dante and his family did not suffer much for wealth, though this claim has also often been argued.

‘Dante’ (1882) by Henry John Stock. ( Public Domai n)

A Purposeful Marriage and Emotional Affair

Dante grew up in his father’s house, losing his birth mother when he was ten and then becoming engaged to a member of the powerful Donati family by the time he was twelve. However, it was around this time that his famed emotional affair with Beatrice Portinari—referenced in every biography of his life and the common thread throughout the entirety of The Divine Comedy —came to fruition.

Though he wed Gemma di Manetto Donati, it was never his wife who haunted his poems and thoughts; it was always Beatrice, who he saw quite often in his adult life yet barely knew, who invaded his romanticized works until her early death around the year 1290.

‘Dante and Beatrice’ (1882/1884) by Henry Holiday. ( Public Domain )

The Political Pull Takes Hold

Following his marriage, Dante became a part of the Physicians’ and Apothecaries’ Guild, ensuring him a place within public city life outside of his father’s reputation. Later in his life, Dante followed in his father’s footsteps and also served in the war between the Guelph and Ghibelline factions, himself also a Guelph.

However, upon the defeat of the Ghibellines, the Guelphs themselves separated into the White and Black Guelphs. Dante became a White, advocating for freedom from the restraining hold of Rome in contrast to the Black Guelphs who continued their support of the Pope, Boniface VIII.

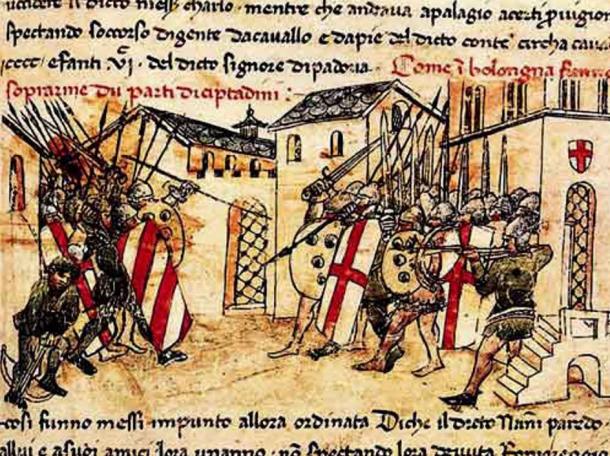

Depiction of a battle between the militias of the Guelph and Ghibelline factions in Bologna, Italy. ( Public Domain )

It was this association that later resulted in Dante’s exile from the city of Florence, following the corrupt government’s accusation against him as a White Guelph, perpetual in length since he refused to pay the fines demanded.

Dante’s Exile and Death

Dante’s exile served to be the most influential aspect of life as his time away from Florentine politics allowed him to shift his literary focuses from only poetry to prose, and during this time his lengthiest and, some would argue, most philosophical work, The Divine Comedy, was written.

‘Dante in Exile’ (1864) by Frederic Leighton. ( Public Domain )

Dante Alighieri died in exile in 1321. Even after given the opportunity to return to Florence, Dante made the choice to stay out of his birth city rather than prostrate himself in front of those who initially forced him out. He was fifty-six years old when he died, most likely from malaria caught during his travels. Dante is buried in the Church of San Pier Maggiore in Ravenna.

Handwritten Notes Discovered 700 Years After Dante’s Death

In July 2021, a Florence-based researcher announced the discovery of a sample of Dante’s handwritten work, after centuries of no one having seen his penmanship. The octogenarian British researcher, Julia Bolton Holloway, believes it is an example of the genius of the celebrated writer.

Holloway taught Medieval Studies at Princeton University in New Jersey, before becoming a nun and running the English cemetery in Florence. Her findings have now been published in a book by the regional authority of Tuscany. These samples were found tucked away in two libraries in Florence and at the Vatican, hiding in plain sight, according to a report published in The Times . They are dated to Dante’s days as a student and scholar in Florence at the end of the 13th century.

According to Holloway, the notes she has discovered “are the only ones written in the so-called cancelleresca script, which Dante was likely taught by his father and are the only ones on cheap parchment, which makes sense given Dante was poorer than his fellow pupils.” There have been no discoveries of Dante’s own original, handwritten version of the Divine Comedy to date. Nevertheless, “Leonardo Bruni, a later Renaissance scholar who saw Dante’s handwriting described it as being similar to the manuscripts I have found,” says Ms. Holloway.

Read Part 2: Dante’s Divine Comedy

Top Image: Fresco of Dante and the Divine Comedy (1465), Domenico di Michelino, Florence cathedral, Italy. Source: Public Domain

Updated on December 2, 2021.

References

Alighieri, Dante and John Ciardi. The Divine Comedy (The Inferno, the Purgatorio, and the Paradiso) (NAL: NY, 2003.)

Alighieri, Dante and Mark Musa. The Divine Comedy, Vol. 1: Inferno (Penguin Classics: UK, 2002.)

Alighieri, Dante and Mark Musa. The Divine Comedy, Vol. 2: Purgatory (Penguin Classics: UK, 1985.)

Alighieri, Dante and Mark Musa. The Divine Comedy, Vol. 3: Paradise (Penguin Classics: UK, 1986.)

Hamilton, Edith. Mythology (Warner Books: New York, 1969.)

Lewis, R.W.B. Dante: A Life (Viking Press: NY, 2001.)

Lewis, R.W.B. “Beatrice and the New Life of Poetry.” New England Review. Vol. 22.2. Spring, 2001, pp. 69-80. http://www.jstor.org.proxy.its.virginia.edu/stable/40243950

Matheson, Lister M. Icons of the Middle Ages: Rulers, Writers, Rebels, and Saints Volume 1 (ABC-CLIO: California, 2012.)

Peters, Edward. “The Shadowy, Violent Perimeter: Dante Enters Florentine Political Life.” Dante Studies, with the Annual Report of the Dante Society . No. 113. 1995, pp. 69-87. http://www.jstor.org.proxy.its.virginia.edu/stable/40166507

Sharma, Indra Datt and Nand Lal. “The Place and Importance of Dante Alighieri in the History of the Medieval Political Thought.) The Indian Journal of Political Science . 6.1. 1944, pp. 28-31. http://www.jstor.org.proxy.its.virginia.edu/stable/42753606

Toynbee, Paget Jackson. Dante Alighieri: his life and works (Nabu Press: South Carolina, 2010.)

Whiting, Mary Bradford. Dante the Man and the Poet (W. Heffer & Sons: Cambridge, 1922.)

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

December 4th, 2021

December 4th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: