The most widely read work of Florentine politician and writer Dante Alighieri, the Divine Comedy dictates a tale of the three realms of the afterlife as believed by the Italians of the Middle Ages. Broken into three parts, Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso are individual cantos—defined as a version of an epic poem that is usually sung—that make up the components of the overall text. As a volume, the Divine Comedy is commonly considered a work of religious poetry, however Dante Alighieri is not shy about revealing his deep understanding of contemporary science, astronomy, and philosophy within the tome as well. It is in part because of his vast array of influences utilized, as well as his lyrical style, that the Divine Comedy was propelled onto the stage of literary masterpieces.

The Divine Comedy and Christian Concept of Afterlife

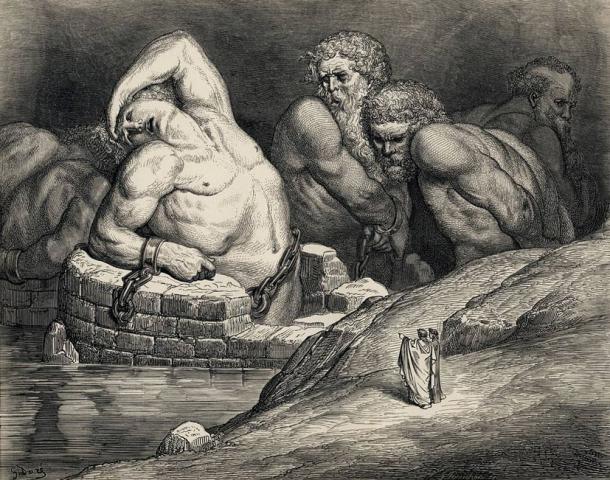

The Divine Comedy is considered by most scholars as an allegory of the different states of afterlife for a soul upon death. In Inferno, Dante discusses the Christian concept of Hell, the place where those who committed sins and crimes suffer for the rest of eternity under the vicious thumb of Satan.

Titans and other giants are imprisoned in Hell in this illustration by Gustave Doré of Dante’s Divine Comedy. ( Public Domain )

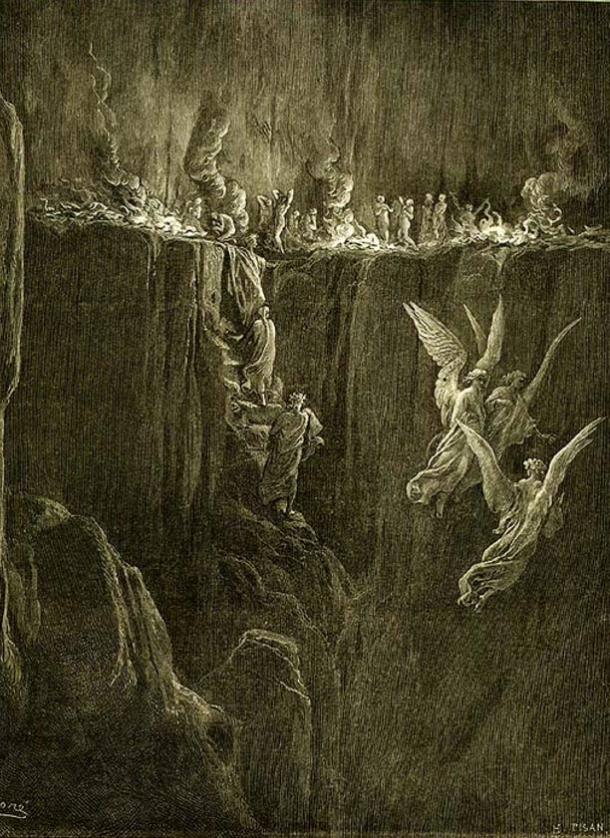

Purgatory reveals those who considered committing crimes but could never move beyond motive to action. The people who rest here are thus neither punished nor praised, but given an opportunity to learn and repent their thoughts by being given labors through which they can surpass their earthly judgments.

Illustration for Dante’s Purgatorio by Gustave Doré. ( Public Domain )

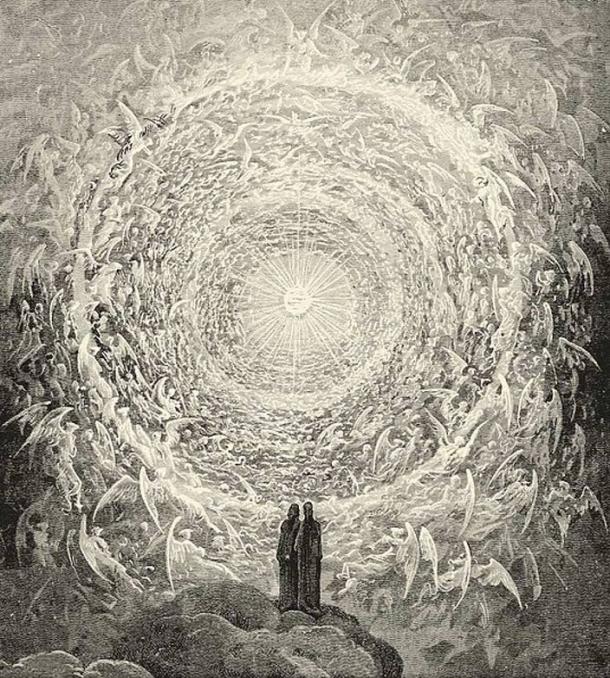

Finally, Paradise is the realm where the good and pure and virtuous are sent, near to the enclosure of God and the Holy Trinity, representing the culmination of a good Christian’s hard work and unwavering faith.

Dante’s Paradise as depicted by Gustave Dore. Dante and Beatrice gaze upon the highest Heaven, The Empyrean. ( Public Domain )

Some of the Virtues and Characters Present in the Divine Comedy

Each of these three afterlives is made up of nine circles, terraces, or spheres, respectively, and one final inner chamber, indicating the importance of the number ten in the Christian view. Within each circle are the committers of a certain deed or the most faithful of a certain virtue, examples of which range from the mythological beliefs of the Greeks—as shown by the vision of Helen of Troy in the lustful realm of Hell—all the way to Dante’s lifetime, where he meets some people he once knew—such as his friend Ugolino (Nino) Viscounti who resides in Purgatory because he committed no sins, but grossly ignored his faith to ensure the well-being of his country.

The count Ugolino and his children in prison, visited by hunger (16th Century) Pierino da Vinci. ( Public Domain )

Dante’s Journeys: A Path to Redemption

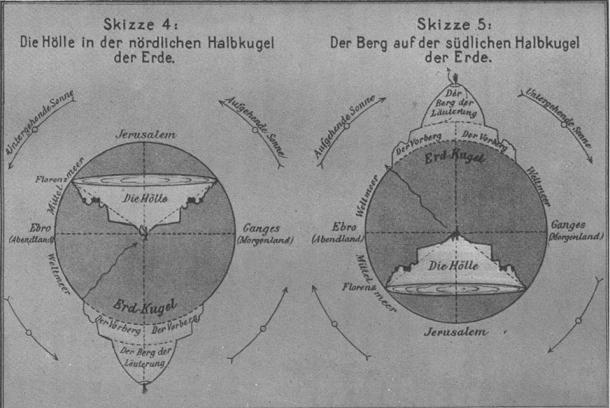

If looking at the world from a side view, it appears that Dante chose to write his text moving from the ground up—beginning in the infernos of Hell, then transitioning into Purgatory and then finally gaining Heaven itself. However, the journey through Hell begins at the top and works its way down, physically moving through the center of the earth to reach the core of all sin and sinners.

Purgatory, in contrast, is designed in the author’s mind as a mountain that must be overcome to reach the Earthly Paradise, also called the Garden of Eden , which lies at the mountain’s zenith.

Heaven is shown in the heavens themselves, the spheres corresponding to astronomical planets and stars, a proper ending for the journey through the earthly realm that one must take to even see it. Dante’s journeys are therefore intended to represent a Christian on the path of redemption, understanding the sins of the world and the consequences that await when one reaches death.

Artist’s interpretation of the geography of the Divine Comedy: the entrance to Hell is near Florence with circles descending to the Earth’s center. Later as Dante passes down, he also moves up to Mount Purgatory’s shores, which are in the southern hemisphere. Then he passes to the first sphere of Heaven, which is at the top (1922), Albert Ritter. ( Public Domain )

The Divine Comedy: Dante’s Grand Finale

Despite Dante Alighieri’s tumultuous political life and the other literary works that took up much of his exiled life, it is the Divine Comedy for which he became known. It is a detailed example of the afterlife beliefs of those of a medieval Italian upbringing, as well as an allegorical record of the concerns about the states of the religious and political spheres of Dante’s Italian contemporaries.

Completed only a year before his death in 1321, the Divine Comedy is the grand finale of thirteen long years of Dante’s life – observing the world around him and contemplating what was waiting on the other side.

Top Image: Dante holding open a copy of the Divine Comedy while gazing towards Mount Purgatory (1530), Agnolo Bronzino. (Detail) Source: Public Domain

Read Part 3: Dante Treks through the Inferno of Satan

By Ryan Stone

Updated on September 1, 2020.

References

Alighieri, Dante and John Ciardi. The Divine Comedy (The Inferno, the Purgatorio, and the Paradiso) (NAL: NY, 2003.)

Alighieri, Dante and Mark Musa. The Divine Comedy, Vol. 1: Inferno (Penguin Classics: UK, 2002.)

Alighieri, Dante and Mark Musa. The Divine Comedy, Vol. 2: Purgatory (Penguin Classics: UK, 1985.)

Alighieri, Dante and Mark Musa. The Divine Comedy, Vol. 3: Paradise (Penguin Classics: UK, 1986.)

Hamilton, Edith. Mythology (Warner Books: New York, 1969.)

Lewis, R.W.B. Dante: A Life (Viking Press: NY, 2001.)

Lewis, R.W.B. “Beatrice and the New Life of Poetry.” New England Review. Vol. 22.2. Spring, 2001, pp. 69-80. http://www.jstor.org.proxy.its.virginia.edu/stable/40243950

Matheson, Lister M. Icons of the Middle Ages: Rulers, Writers, Rebels, and Saints Volume 1 (ABC-CLIO: California, 2012.)

Peters, Edward. “The Shadowy, Violent Perimeter: Dante Enters Florentine Political Life.” Dante Studies, with the Annual Report of the Dante Society . No. 113. 1995, pp. 69-87. http://www.jstor.org.proxy.its.virginia.edu/stable/40166507

Sharma, Indra Datt and Nand Lal. “The Place and Importance of Dante Alighieri in the History of the Medieval Political Thought.) The Indian Journal of Political Science . 6.1. 1944, pp. 28-31. http://www.jstor.org.proxy.its.virginia.edu/stable/42753606

Toynbee, Paget Jackson. Dante Alighieri: his life and works (Nabu Press: South Carolina, 2010.)

Whiting, Mary Bradford. Dante the Man and the Poet (W. Heffer & Sons: Cambridge, 1922.)

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

September 2nd, 2020

September 2nd, 2020  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: