On October 5, 1961, in a letter to his editor, James Baldwin writes from within Israel: “it has become very important for me to assess what Israel makes me feel.” Continuing in the correspondence, he begins to describe the relational feeling which his experiences in Israel give him, stating:

“In a curious way, since it really does function as a homeland, however beleaguered, you can’t walk five minutes without finding yourself at a border, can’t talk to anyone for five minutes without being reminded first of the mandate (British), then of the war—and of course the entire Arab situation, outside the country, and, above all, within, cause one to take a view of human life and right and wrong almost as stony as the land in which I presently find myself—well, to bring this thoroughly undisciplined sentence to a halt, the fact that Israel is a homeland for so many Jews (there are great faces here, in a way the whole world is here) causes me to feel my own homelessness more keenly than ever.”

Lacking the feeling of homeness, or embracing of an internal homelessness while in Israel becomes the backbone for a series of letters and unpublished writings by Baldwin which explore the Israeli-Palestinian “situation.” Baldwin becomes an important, interesting figure in analyzing exactly what it is that the Palestinian-Israeli conflict has historically made Black Americans feel, which has been able to cultivate decades-long solidarity between the two oppressed groups in activist circles.

Baldwin’s interest and later static political positions surrounding the conflict, give us a curiously powerful backdrop in looking at Black and Palestinian solidarity, because it is one explored through Baldwin’s poetic, observational writing. Baldwin dives past simple fact and positionality to attach a sentiment to a politic; his views on Israel shifted drastically after spending extended time traveling in the region. As Keith P. Feldman states in his 2015 book ‘A Shadow Over Palestine: The Imperial Life of Race in America”, “If this (Israel) was what home meant for modernity’s others, Baldwin will have none of it.”

Truly, this manifestation of sentimental “home” and the emotions that accompany is deeply resonate with the Black diasporic experiences that Baldwin represents. If Baldwin saw with his own eyes the denial of home to the Palestinians, and was able to relate that to the troubling yet always relevant difficulty that diasporic Black people have with the entire concept of home, then this means he was able to make his linkage to the conflict one of sentimental, or almost spiritual, connection. The concepts of home, land, and space have similar connotations Africans, both diasporic and within African nations, as they do for Palestinians. We have both, on several occasions, been violently removed from land, colonized on our land, and had our beliefs of land and property challenged by dominant forces.

The late 1960s began to function as a breeding ground for Black and Palestinian solidarity which one could argue occurred at the height of the Black Power movement, along with several decolonial Pan-Africanist movements taking place internationally. In 1967 the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) led by revolutionary Stokely Carmichael began to move into a much more radical direction, and made the bold decision to issue a statement of “unreserved support for the self-determination of the Palestinian people.” SNCC played a central role in the Freedom Rides, sit-ins, and 1963 March on Washington, and them moving left towards positions based on strong anti-war politics and international solidarity signaled a deeply influential chance for anti-Zionist activism to grow into Black communities. SNCC’s influence across the U.S. south represented discussions of Black-Palestinian solidarity moving into the conversational sphere of Black America, as SNCC’s biggest role tended to be door-to-door voter registration, providing free political education, and other interpersonal field work which aimed at spreading their politics while making political moves. With Palestine now added to their official stances, it was able to move into the Black conscious quickly.

It should come at no surprise that around this same time the Black Panther Party also took on a stern pro-Palestine position. This is largely due to the Black Panther’s conceptualization of Black Americans as “a colonized people within a colony,” and understanding the colony they existed in also happened to be the world’s imperial, or hegemonic, power. With the Black Panthers having a strong Pan-Africanist influence guiding their evolving political Marxist-Leninist-Maoist ideology, they saw the Palestinian struggle as almost synonymous with the international Black struggle.

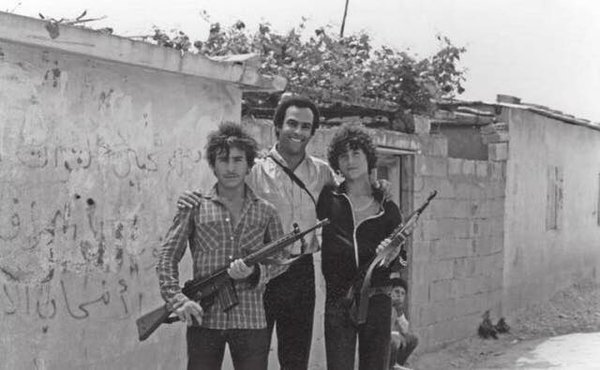

Huey P. Newton, co-founder of the Black Panther Party, at an unknown Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon, 1980. (Photo: Dr. Huey P. Newton Foundation Inc./Department of Speical Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries)

Free The Land! “By Any Means Necessary,” poster by Emory Douglas, former Minister of Culture of the Black Panther Party, 2010.

With “food, clothing, work, shelter, and peace of mind” being the underlying needs expressed by the Black Panther Party’s ideology, as cemented by their official ten-point platform, it only makes sense that they saw the connections with Palestinians as deeply rooted and integral to their organization. In 1970 organization co-founder Huey P. Newton issue a statement saying the Panthers “support the Palestinian’s just struggle for liberation one hundred percent.” That same year, Newton provocatively proclaimed the Panthers were “in daily contact with the PLO,” and would be the backdrop to a trip to Lebanon years later where Huey visits a Palestinian refugee camp and meets with Yasser Arafat. Huey’s public image at this time was one of militancy, and his growing contact with Palestinian activists only furthered this image. Popular representations of him and art by Emory Douglas often showed Newton with guns in his hands, looking stern in the face, and he was branded underneath the masculine, militant air that surrounded the Black Panthers

Also important to note within this Black-Palestinian anti-Zionism nexus is Malcolm X’s two days spent in the Gaza Strip in 1964, which would profoundly influence his future politics and writings. In his essay “Zionist Logic,” Malcolm discusses reflectively his thoughts on Zionism, and touches on three main points: camouflage, dollarism, and Messiah. He examines that Zionists have attempted to “camouflage” their form of colonialism as “benevolent,” points out that Israel’s placement successfully secures the financial interests of Western imperialists, and then questions who the Messiah that, religiously, is supposed to lead them to their promised land? All three of these subjects are specific in the context of Palestine, however, translate greatly into the Black political sphere. Malcolm’s point on ‘camouflaged’ colonialism resonates deeply with both diasporic and continental Africans, who are on either stolen or occupied land; his point on imperialism and “dollarism” has a clear connection to the historic exploitation of Black bodies globally, whether through slavery or other forms of capitalistic wage theft; and his final point on questioning the religious justification of Zionism conjures the relation to modernity’s constant religious apologism for white supremacy.

Like Baldwin, it is in seeing first-hand the suffering that Palestinians were experiencing that moved Huey, Stokely, and Malcolm even further on their positions of support. If Baldwin was able to place some sort of sentiment, or feeling, between the Black and Palestinian struggles globally, then Huey was able to merge it with a Black militancy bent on decolonial struggle. Stokely was able to bring the issue to the people via one of the most influential Black southern organizations of the time, and Malcolm brought it to a seemingly spiritual level in his contemplations of anti-Zionist internationalism. These iterations of influential Black activists fanning the fires of solidarity are important, because they allude to the greater trend of shared struggles between both communities.

One might ask where does Black and Jewish solidarity fit into the equation, and why hasn’t it panned out to become as large and sustaining as the Palestinian solidarity has, and the answer is partly due to the epistemological mechanisms of whiteness. Whiteness, as a social construct, is often seen as contextual and/or situational with Jewishness, and therefore can be seen as oppositional to Blackness. To an extent, many sociologists posit that Blackness is antithetical to whiteness, thus that certain communities of Jewish background have been able to in recent history gain their “white card” as some call it, something Black populations and many Arab populations will never be able to do, this may thwart Black-Jewish solidarity from rising as highly as its Palestinian counterpart has historically.

Of course not to be dismissed is anti-Semitism within some Black communities, which runs parallel to anti-Blackness in many Jewish communities. Baldwin discusses anti-Semitism in his 1967 essay “Negroes Are Anti-Semitic Because They’re Anti-White,” explaining that anti-Semitism flourished because of people in Black communities, particularly Harlem, witnessed Jewish communities assimilate into whiteness through racial, class stratification. The Jewish individual became synonymous within Harlem’s majority-Black community with interpersonal exploitation, as Baldwin puts, they were seen as the “tradesmen, rent collectors, real estate agents, and pawnbrokers; they operate in accordance with the American business tradition of exploiting Negroes.” And while Harlem was just one place, its influence in the Black world went unmatched for some time, and this stereotype began to manifest and spread in various capacities.

Anti-Semitism in Black communities is almost overstated, overemphasized, or exaggerated, while anti-Black racism in Jewish communities (and Christian communities, for that matter) is constantly ignored. This often creates even more tension between the two communities. And this is not to say that solidarity between Black and Jewish communities internationally is nonexistent, to the contrary. There is a strong history of the two communities, which do overlap, too, coming together to effect justice. However, epistemologically, the struggle for Black liberation has often crossed paths with the anti-Zionism movement and doesn’t seem to be diverting from that path anytime soon.

It can also be suggested that some integral part of the Black identity, which is predicated on a history of shared struggles and resistance to white supremacy, is linked to the Palestinian identity. In Sohail Daulatzai’s “Black Star, Crescent Moon: The Muslim International and Black Freedom beyond America,” he illustrates that the “Muslim terrorist” and “Black criminal” tropes became almost inextricably linked to Arab and Black identity around the same time. He states that these two tropes became the “twin pillars” in solidifying post-Civil Rights era state repression in the 70s and 80s, coinciding with the 1972 Olympics where Palestinians stormed the Israeli athletes’ dormitories, causing international outcry, and the state-demonization of hip-hop culture as “violent.” Moreover, the context which these tropes rose to prominence surrounds Palestinian and Black activists still today, and influence acts of police brutality, fuel mass incarceration, perpetuate media misrepresentations, and contribute to the dehumanization of the two identities in both the US and Israel. Simply put: the unfounded vilification, both historically and contemporarily, of the Palestinian and Black identities lends itself to position the Palestinian liberation struggle in partnership and even synonymous with the struggles for Black liberation. If, as historian Seneca Vaught often says, the Black diaspora is more of a state of mind than actual geographical location, then Palestine has a unmoving place.

Palestinians take part in a ceremony to unveil a sculpture of the first democratically elected South African president and anti-apartheid leader Nelson Mandela, in the West Bank city of Ramallah, Tuesday, April 26, 2016. Palestinians honored Mandela unveiling his statue on a square in Ramallah, on South Africa’s Freedom Day that is observed annually to commemorate the first post-apartheid elections held on April 27, 1994. (Photo: Shadi Hatem/APA Images)

These historical intricacies of shared struggle on emotional, militant, spiritual, and identity levels are the same reasons why Black Americans lent such strong solidarity to South Africans during the anti-Apartheid Movement. That we were able to not only find links and connections between Jim Crow and South African Apartheid, but see material evidence of the sameness of the two attached on both physical and emotional levels allowed us to perform maximum solidarity. It is the same with Palestine; we are able to perform and perpetuate deeply resonating solidarity with the Palestinian cause for self-determination because it is a struggle not only familiar with us, but attached to us.

The solidarity between various movements for Black liberation and Palestinian movements exists today, with popular Black activists like Angela Davis, Cornel West, Beverly Guy-Sheftall, and others keeping it alive through public support of the BDS movement and writing which explores the connections between the two communities. One of the most popular books of 2016 was Angela Davis’ “Freedom is a Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the Foundations of a Movement” which looks at the interconnectedness of international liberation struggles in contemporary times. The book’s opening essay focuses on collective struggles against capitalist individualism and takes particular time to discuss the Black Power movement, the global prison-industrial-complex, and South African Apartheid movement, all in relation to Palestine.

Along with books connecting the two struggles popping up with increasing frequency, we’ve also begun to see a re-invigoration of Palestinian issues in various movement’s platforms. The Movement for Black Lives added solidarity for Palestine to their official platform demands, calling Israel an “apartheid state” that perpetrates “genocide” on the Palestinian people. Famed Palestinian activists Rasmea Odeh and Linda Sarsour both played key roles in the 2017 Women’s March, which advocated for global women’s liberation from an intersectional standpoint. Several Black activists attend delegations to Palestine yearly (a famous one featuring well known Indigenous and women of color feminists occurred in 2011, which sparked international attention) and continue to cultivate the growing relationality of these issues. The growing issues of Black oppression, whether police brutality, mass incarceration increased ICE raids, land confiscation, or poverty do not seem to be slowing down anytime soon and signal a growing solidarity with Palestinians, whose struggles also seem to be growing similarly.

All of this is to say, that the solidarity between Black and Palestinian people internationally is rooted in a profound historical framework, one of shared struggles and collective identities that push us to challenge notions of international solidarity. Baldwin wrote that he saw the “treatment of the Arabs at the hands of Israel” and it threw him so much towards a connected feeling he could not ignore, he stated he would choose homelessness over what he witnessed familiarly. Angela Davis finishes the first chapter in “Freedom Is A Constant Struggle” by stating that “this is precisely the moment to encourage everyone who believes in equality and justice to join the call for a free Palestine.” Truly, thanks to freedom fighters like her, and Baldwin, and Newtown, and Carmichael, and the magnitudes of other Black revolutionaries who set such a strong historical backbone for Black and Palestinian solidarity to rest our current struggles against, we can continue to embrace solidarity in this long walk to freedom.

Source Article from http://mondoweiss.net/2017/05/historical-palestinian-solidarity/

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

May 19th, 2017

May 19th, 2017  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: