During the early stages of my journalism career, I took a deliberate and conscious decision to abstain from writing about the infamous Sabra and Shatila Massacre.

One of the many chapters of the harrowing Lebanese Civil war, the massacre was something I grew up learning about as a Palestinian refugee in Lebanon, living in Bourj El Barajneh refugee camp, just around 1 km away from Sabra and Shatila.

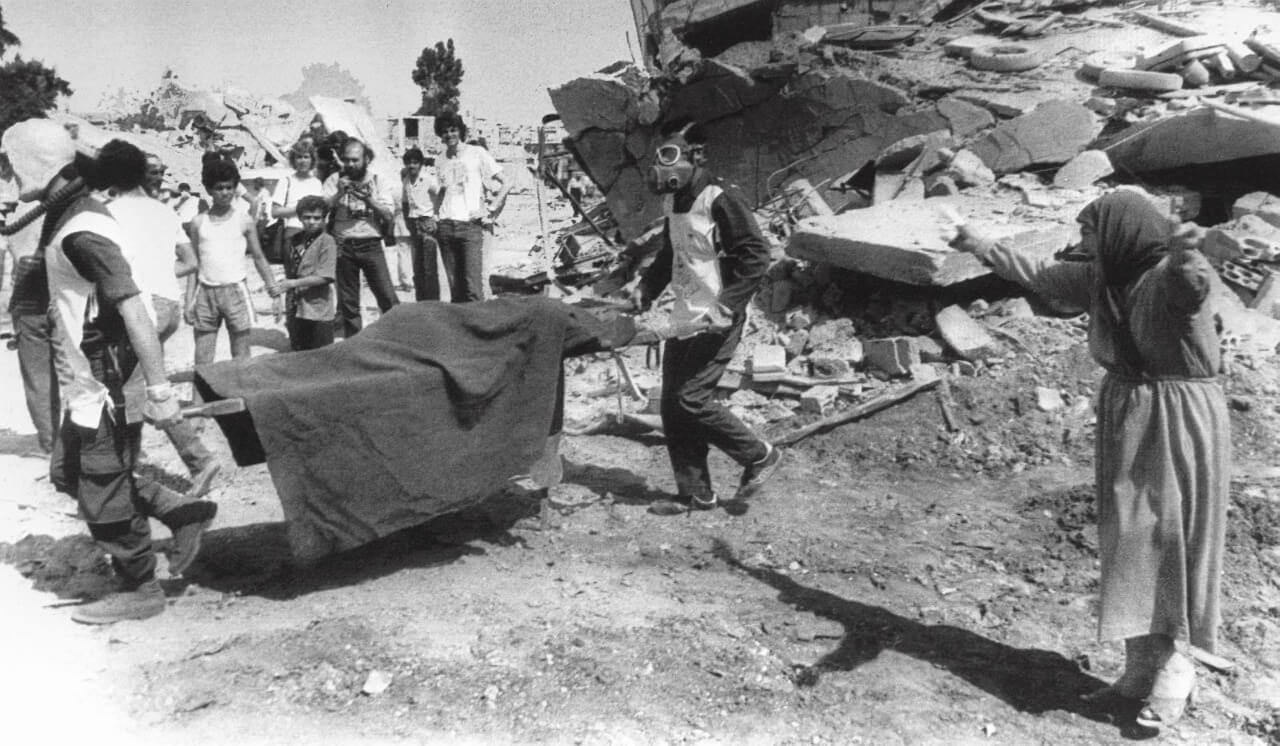

Eleven years before I was born, backed by the invading Israeli military forces, the Lebanese Phalange militia managed to slaughter somewhere between 2,000 and 3,500 civilians, primarily Palestinian refugees dwelling in Sabra, a Lebanese neighborhood that overlaps the Palestinian refugee camp of Shatila, to the south of the Lebanese capital of Beirut. In spite of the fact that the massacre took place in that particular camp, its ghost has haunted all of the Palestinians across different refugee camps in Lebanon. I remember vividly when I was growing up, every year around the anniversary of the massacre, during the coffee gatherings that my mother hosted, the women would discuss their memories of the massacre in horrific detail.

“Young girls were raped with Pepsi glass bottles, and young men were chopped by machetes into pieces,” one woman said, as I closed my ears so tightly, not wanting to hear the rest.

For the first time in a long while, I made the decision to visit Sabra and Shatila camp as a journalist this year, on the 40th anniversary of the massacre. I chose to enter from the al-Rehab area of Sabra, where 40 years ago, Israeli troops were stationed, as they blocked all entrances and exits to the area while the Phalangist Militias entered the camp and began slaughtering people indiscriminately.

The streets of the area have changed immensely since the end of the civil war in 1990. Now home to crowded and lively street markets, I picture what these streets looked like 40 years ago, when they were used as the starting point of the Phalange militia men. As I go further into Shatila camp through the narrow alleyways, dotted with kiosks, shops, and weathered homes, I try not to recall the images that spread in the aftermath of the massacre, showing piles of butchered bodies on both sides of this road. As I walk, I step on a spot of blood coming from a nearby local butcher, and an eerie feeling runs in each vein of my body.

I am not a resident of this camp, but since Palestinian refugee camps share similar features, the narrow dark alleys, jumbled electric cables hanging from one wall to another, and the sounds of people speaking in Palestinian dialects, I felt a sense of home, and was comfortable to move around.

“We have talked about this for so long now, but nobody cares that we were slaughtered like chickens…I am not going to do this right now, or ever again.”

A Palestinian woman who survived the Sabra and Shatilla massacre

I approach two women sitting on the doorstep to their house. Since the beginning of the fuel and power crisis in Lebanon, this has been the refugees’ way to attain some light and relatively cool air during the blistering summer heat.

“May I talk to you about the massacre?” I ask. In a quick-handed gesture, they ask me to leave.

“We have talked about this for so long now, but nobody cares that we were slaughtered like chickens,” one of the women says, frustrated. The other adds, “the only thing I have to say is that I remember all the details. I cry because of the horrific memories, I live with this pain for days, and sometimes months.”

“I am not going to do this right now, or ever again,” the first woman says. And so I move on, making my way through the camp.

Next to an office of one the Palestinian political factions, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), I find an elderly man sitting on a chair right in front of his home, kneeling on his cane.

He introduces himself as Abu Wassim. He’s 75 years old, and agrees to talk to me about the massacre. He was 30 years old when it happened, and remembers it like it was yesterday.

“I wish I died back then, at least I would have been a shahid, not someone thrown in a camp living this life,” he said. Shahid is the Arabic word for martyr, the title given to those killed in the massacre.

“They invaded the area right after sunset,” Abu Wassim remembers. “Just like these days, the camp was completely sinking in darkness, with no electricity. The Israeli flare shells were lighting the sky, but on the ground, we did not know what was happening.”

“The massacre was going on but in complete silence,” he continued. “Thankfully, none of my family members was harmed, because they were not in the camp at the time. I only survived by mere luck. I stayed here in my house, I never left. They did not reach this area, that’s it.”

I continue to walk in the winding alleyways of the camp, now home to an estimated 8,000 Palestinians and an unknown number of (low income) people from different nationalities, living in an area of approximately one square kilometer. I meet Mohammad Ismail, another eyewitness and a survivor of the massacre.

“Look dear, do not ask me about my family members that I lost, I do not want to talk about them,” he told me sharply. “But I want the world to know that we were left unprotected, we did not have any guns to defend ourselves.”

The invasion of the camp was predicated on the allegations by the Israeli army that the camp was housing thousands of Palestinian fighters belonging to the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). But residents of the camp, and subsequent investigations, found these claims to be largely untrue, as PLO fighters had largely pulled out of Western Beirut by the evening of September 16, when the massacre began.

“All of the fighters had already left with the thawra (the Revolution). We buried some of the few guns that remained, and we were left to meet our gruesome destiny,” Ismail said.

“It wrenches my heart that we did not even know what was happening. I was standing right here with some friends right after maghrib prayer. We started to see people running away from the outer entrance of the camp. They were wounded, and nobody knew what was taking place,” he continued. “We were in complete shock.”

“If not here, then in the afterlife. But they will be held accountable one day.”

Ismail

When I asked him about his thoughts, that until today nobody has been held accountable for what happened during those two nights and days, Ismail could not say a word, but he turned his face away from me with his eyes full of tears.

“If not here, then in the afterlife. But they will be held accountable one day.”

During the commemoration of the massacre, many foreign supporters from around the world visit the camp to participate in memorial events next to the mass graveyard of the victims, which sits by the main entrance of Sabra neighborhood. That is how I met Louise Norman, a Swedish anesthesia nurse who arrived as a volunteer in 1982 just a few weeks before the massacre.

“I try my best to come and participate in the memorial of the massacre whenever I can. What happened back then and what I saw was unimaginable,” she told me. I asked her if there are any precise incidents that she cannot forget about. “I’d rather share with you this memory that is dear to my heart,” Norman said.

“There was this boy, he was only 10 years old. All of his family members were slaughtered except for an older brother of his who happened to not be at home and he actually hid underneath the bodies of his killed siblings,” she remembered.

“His brother came back home and found him injured but still alive. I took care of him until he was better. Over the years I lost track of them, but just a few years ago, I found out they were in the US. I traveled to them and visited them. It was heartwarming.”

After the commemoration ceremony, I wrapped up my day in the Shatila refugee camp. It was a strange feeling, after all these years of avoiding the story, to finally allow myself to revisit this collectively traumatizing memory.

To me, it had always seemed unsettling, the way journalists approach topics related to the Palestinian cause, particularly the theme of Palestinian refugees in Lebanon. It did not feel right to annually and constantly reopen the wounds of the victims for the sole purpose of producing a journalistic material, and I felt that as I walked through the camp and spoke to some of the residents, who were clear about the pain that was caused by remembering the massacre. I also felt that through the story, and the peoples’ retelling of their history, I was able to reflect their agony of being a survivor of this massacre. I was not an outside journalist looking in, but rather I was discovering a part of my larger story of being a Palestinian refugee in Lebanon.

This movement needs a newsroom that can cover all of Palestine and the global Palestinian freedom movement.

The Israeli government and its economic, cultural, and political backers here in the U.S. have made a decades-long investment in silencing and delegitimizing Palestinian voices.

We’re building a powerful challenge to those mainstream norms, and proving that listening to Palestinians is essential for moving the needle.

Become a donor today and support our critical work.

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

September 19th, 2022

September 19th, 2022  Awake Goy

Awake Goy

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: