A team of Italian archaeologists exploring ruins connected to the legendary Neo-Assyrian Empire have discovered an ancient industrial wine press. Dating to approximately 700 BC, the remains of the wine press were found at an archaeological site known as Khanis, which is in the Duhok governate in the Kurdistan region of northern Iraq.

“This is a quite unique archaeological finding, because it is the first time in northern Mesopotamia that archaeologists are able to identify a wine production area,” Daniele Morandi Bonacossi, a University of Udine archaeologist, explained to CNN. Bonacossi is also the director of the Land of Nineveh Archaeological Project carried out by the Italian Archaeological Mission in Assyria (IAMA) of the University of Udine who has aimed at excavating in Dohuk to “record, conserve and promote the incredible cultural history” of the region

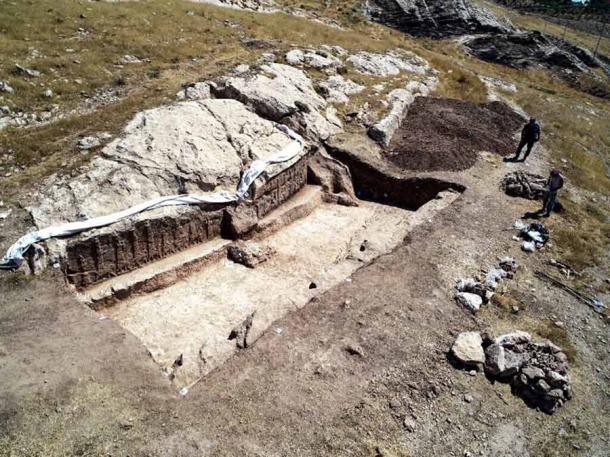

The Khanis site is best known for striking rock reliefs found carved overlooking the River Gomel Su, near where the wine press has been discovered. ( University of Udine )

Assyrian Wine Press and the Assyrian Love of Wine

Carrying the distinction of being one of the world’s earliest empires, the Assyrian state once ruled over an expansive region that included all of modern-day Iraq, plus sections of Iran, Kuwait, Syria, and Turkey. The empire was ruled by a class of wealthy elites with sophisticated tastes, and decoded Assyrian writings suggest they eventually developed quite a passion for high-quality wine.

“In the late Assyrian period, between the 8th and the 7th century BC, there was a dramatic increase … in wine demand and in wine production,” Bonacossi explained on CNN. “The imperial Assyrian court asked for more and more wine.”

In addition to enjoying it for its flavor, Assyrian royalty and aristocrats apparently made use of wine in their ceremonial practices. The Assyrians were polytheistic to the extreme, meaning they had many different gods they needed to honor in order to assure the continued prosperity of their empire.

Previous studies of botanical remains in the region show that the size of local vineyards increased in the seventh and eighth centuries BC. This would be consistent with a rising demand for wine among the more exalted social classes.

The archaeologists discovered pits carved into the stone which were used as a wine press, to extract juice from grapes for wine production. ( University of Udine )

Making Wine Inside a Mountain

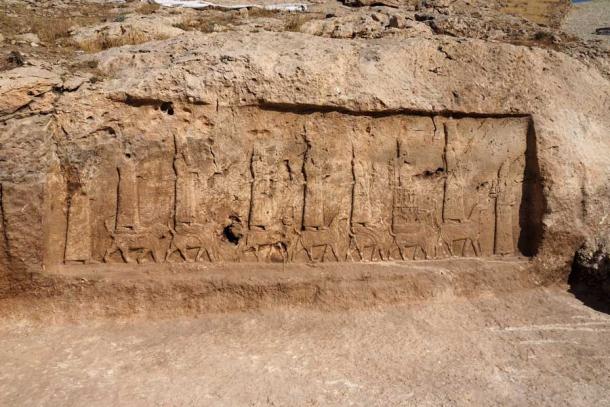

Until now, Khanis has been best known for the large, striking rock reliefs that were carved into bluff faces overlooking the River Gomel Su. The elaborate rock images show Assyrian kings in prayer to their gods, and also feature carvings of various types of animals.

The reliefs were created to celebrate the construction of an interlocking system of canals, which were built in the early seventh century BC. The canals supplied water to Assyrian citizens in the empire’s capital city of Nineveh 30 miles (50 km) away, and to those living in other parts of modern-day northern Iraq as well.

Like the reliefs that have brought Khanis so much attention, the wine press was also carved into the mountainside. Inside square-shaped artificial caves, laborers would crush piles of grapes beneath their feet, after which the grape juice would run out through drains into collecting basins carved into the rock face at lower levels. The grape juice would be scooped out into large jars and relocated to storage areas to ferment.

Overall, the wine press at Khanis included 14 separate installations, and was extensive enough to produce prodigious quantities of wine after every harvesting season. The Italian researchers believe they may have uncovered the oldest industrial wine operation ever constructed in that part of the world, or possibly in any part of the world. It is just the second such wine press discovered in the Middle East, and as of now nothing similar has been found anywhere else.

Archaeologist Daniele Morandi Bonacossi and one of the panels of Assyrian carvings unearthed at the Khanis archaeological site in the northern Kurdistan region of Iraq where the industrial wine press has been found. (Alberto Savioli / Land of Nineveh Archaeological Project )

The Imperial Vision of King Sennacherib

Antiquities authorities in Duhok have been cooperating with the ongoing excavations at Khanis, which are designed to illuminate the accomplishments of the great Neo-Assyrian Empire. “The history of this press dates back to the period under the reign of King Sennacherib,” explained Baikaz Gamel Eldin, who serves as head of antiquities in Dohuk, in Local12.

Sennacherib, who ruled the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 705 to 681 BC, was a larger-than-life figure noted for two things: his military campaigns against his neighbors and rebellious client states, and his grand and ambitious construction projects. Throughout history, megalomaniacal leaders have frequently sought to demonstrate their importance through military conquest and by building huge, monumental structures that would be used and admired for centuries. Sennacherib represents an early example of this pattern.

The rock reliefs of Khanis were ordered by Sennacherib, who also initiated the construction of the extensive canal system they were installed to acknowledge and celebrate. Sennacherib also launched several new building projects in the Assyrian capital city of Ninevah. As a part of his ongoing urban development initiative, he built new roads and bridges and installed many impressive gardens . He also built an 80-foot-thick (25 m) fortification wall that surrounded the city and protected it from outside invaders (a constant worry of empire-builders).

Undoubtedly his greatest achievement in construction was the spectacular palace complex he built to honor his own greatness. The so-called “Palace without Rival” was said to measure 1,500 feet (500 m) from end-to-end. The materials used in its construction included a mixture of mundane and precious materials, such as mud-brick, stone, ivory, bronze, gold, cedar, and pine.

Slabs of alabaster engraved with carvings of Assyrian gods and images of Sennacherib’s military campaigns were installed on the walls of the palace temples, living quarters, and administrative buildings. The outer grounds of the complex featured large orchards and many samples of plants and trees retrieved from different parts of the empire.

The remains of his spectacular palace were first discovered by archaeologists in 1840. Excavations have continued to this very day, which is a testament to the enormous size and complexity of the monumental complex Sennacherib built in honor of himself.

The rock reliefs of Khanis, ordered by Sennacherib, were created to celebrate the construction of a canal system in the seventh century BC. The images show Assyrian kings in prayer to their gods, as well as animal carvings. ( Land of Nineveh Archaeological Project )

Toasting the King and the Assyrian Wine Press at Khanis

It is not known if Sennacherib actually ordered the construction of the wine press in Khanis. However, given his apparently obsessive need for recognition, it would hardly be surprising if he did. As the only industrial-sized winemaking facility in Mesopotamia in the seventh century BC, this ancient Assyrian wine press would have stood as yet another example of Sennacherib’s greatness and of the magnificence of his empire.

Top image: Excavators work at the site of the archaeological dig on the eastern bank of the Faidi canal, just north of Mosul, where evidence of an Assyrian wine press has been discovered. Source: The Kurdish-Italian Faida and Khinnis Archaeological Project

By Nathan Falde

Related posts:

Views: 0

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

November 4th, 2021

November 4th, 2021  Awake Goy

Awake Goy  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: